山形国際ドキュメンタリー映画祭で行われている「ヤマガタ映画批評ワークショップ」。映画祭というライブな環境に身を置きながら、ドキュメンタリーという切り口から、映画について思考し、執筆し、読むことを奨励するプログラムとして好評を博してきました。今回、この批評ワークショップがインドネシアのジョグジャカルタで開催されました。「ヤマガタ映画批評ワークショップ in ジョグジャカルタ」より、Permata Adindaさんによる批評をご紹介します。英文のままの掲載となること、ご了承ください。

Tracing One’s Sexuality: Agustina Comedi’s Silence Is a Falling Body

Permata Adinda (Indonesia)

Sexuality is not always a fixed thing, recent studies suggest. Rather than being easily classifiable as either “homosexual,” “heterosexual,” or “bisexual,” sexual preference has proven to be more complex. It might change over a lifetime and be dependent on different situations. The Centre for Addiction and Mental Health and the American Psychiatric Association state that sexual orientation may be fixed and continuous throughout the lives of some people, and is fluid, or changes over time, for others. Lisa M. Diamond, who wrote a book about sexual fluidity (Sexual Fluidity: Understanding Women’s Love and Desire), argues that traditional labels for sexual desire are inadequate. Her research contains examples of women who identify as heterosexual but find themselves falling in love with women. The word bisexual does not truly express the nature of such a person’s sexuality.

Despite the recent updates in sexuality studies, such discoveries still have not been depicted very often in films. Many films that have addressed homosexuality mainly dwell on the process of coming out, or the identity and social problems related to the characters’ sexuality — framing sexuality as something that always stays in one path. Call Me by Your Name, a feature-length fiction film set in Italy in 1983, portrays the journey of a boy discovering and making sense of his homosexuality. God’s Own Country depicts a growing romantic relationship between two men who live in a conservative, homophobic society. There are also The Handmaiden, Malila The Farewell Flower, Moonlight, Thelma and many more recent films portraying homosexuality. Yet it is still difficult to find sexual fluidity acknowledged and depicted in films.

That is why Agustina Comedi’s Silence Is a Falling Body, a documentary that traces the life of an Argentine married father who had been keeping secrets about his sexuality throughout his marriage, is an important film. While the film looks for information about its central figure’s past life as homosexual, it also finds proofs of his love for his wife and daughter — a hint of his sexual complexity, matching the latest studies of human sexuality.

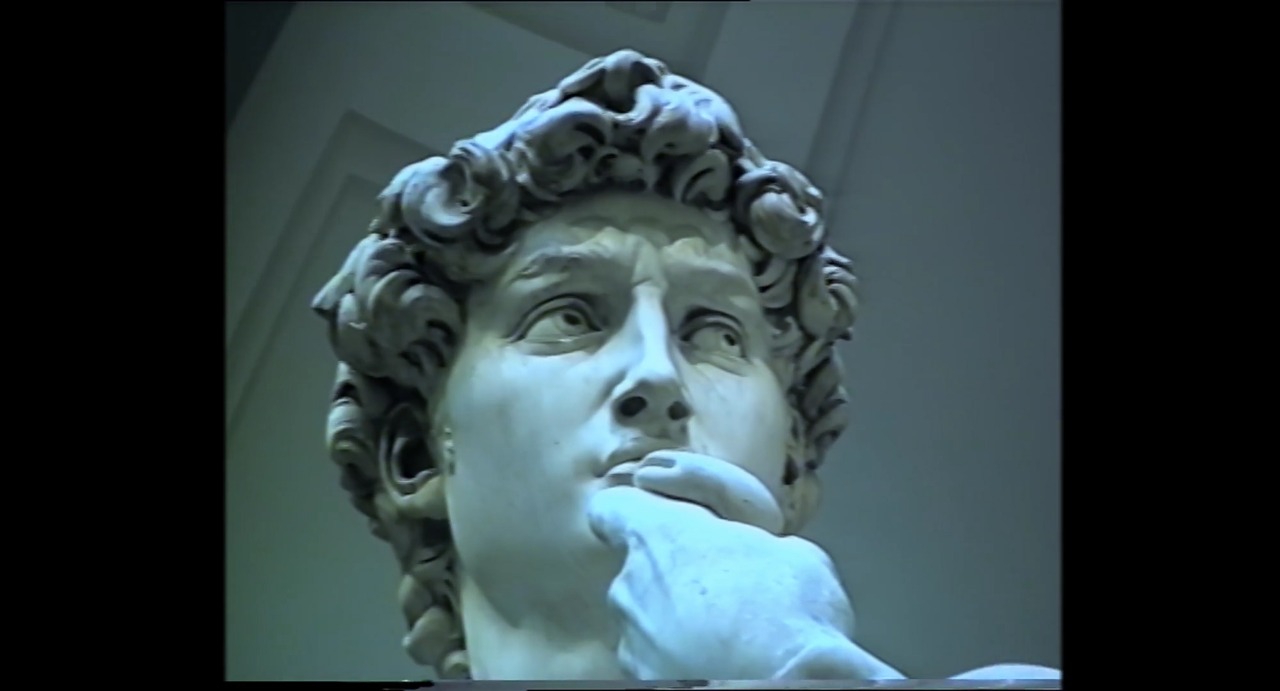

Jaime was a homosexual. The film makes sure we acknowledge that from the beginning. Silence Is a Falling Body begins with Jaime’s home-movie footage of a naked male statue, zooming on its intimate body parts: a hint of Jaime’s sexual attraction towards men. We also hear stories from people about his relationship history with men: about his first boyfriend, his 11-year-long relationship with a man, and his psychologist diagnosing him as gay. The film leads us to question his motive in choosing, later in life, to marry a woman, by whom he had a daughter. Did Jaime marry against his will; was it something he was forced to do, considering the homophobic social condition he was under at the time? Or was it something he did voluntarily and wholeheartedly?

We could argue that Jaime lived in an era that was difficult for LGBT, which influenced his decision to get married and to live in a normal way according to the society standard. Argentina had a long history of oppression and violence against the LGBT community before the 1980s, the era of Jaime’s generation. The film interviews people who had the experience of being discriminated against and tortured by the society and the state. One person had to make up things during a police interrogation to avoid being electrocuted. Another person was taken to a mental hospital and returned only to endure considerable trauma.

However, while it could be true that Jaime married because of the conditions of his society, we know that he also had a happy marriage. Many of the home movies Jaime made were about his daughter — playing violin, singing, dressed in costume, playing with other kids. He even filmed the naked body of a pregnant woman in a highly intimate way, indicating his love for his wife. A person who was close to him reveals his growing habit of buying women’s jewelry and looking tenderly at baby’s clothes in a store before finally buying them, indicating his intention to marry in the first place. His wife even still brings a photograph of him everywhere — even though she found out about his homosexuality at one point in their marriage — revealing the romantic affection they have between each other.

Instead of arguing that he was sexually repressed throughout his marriage, the film provides no explicit statement or conclusion regarding Jaime’s sexual state. It also does not perceive Jaime’s situation as an unfortunate thing. Through the images he filmed and other people’s impressions of him, we instead see Jaime as a loving person who loved to hug people in the open street and smile at the camera. Filmmaker Agustina Comedi, who is Jaime’s daughter, distances herself from the film, letting the recordings of her father and the people who were close to him speak about him.

Jaime’s behavior as portrayed in the film — that of someone who seems to be enjoying his marriage rather than feeling forced into it — is actually in line with the results of Diamond’s latest study in 2014 about men’s sexuality. Sampling 300 Salt Lake City residents who were equally divided among those who self-identified as homosexual, bisexual, and heterosexual, the study shows that 31 percent of self-identified gay men reported having developed romantic feelings for women in the previous year. The study also reveals that 40 percent of gay men reported some attraction to the opposite sex in the previous year, and 20 percent of gay men reported wanting to have sex with a woman during the previous year. Jaime’s life also has parallels with the case of Chirlane McCray, an American writer and political figure who married a man in 1991 — 34 years after writing an essay about her coming out as a lesbian. She stated that she is more than just a label — indicating her reluctance to be identified as “bisexual” or “heterosexual” — and that she did not consider herself sexually attracted to men, but rather attracted to her husband only.

The view of Silence Is a Falling Body regarding sexuality might also be implied in the words of the filmmaker’s son at the end of the film: “To be free means not having to be trapped in a cage.” The scene is the only one in the film to be shot in the 16:9 ratio. While the 4:3 ratio of all the previous scenes might imply the intention to blur the difference between which images were shot in the past and which ones are in the present — creating the illusion that all of them belong to the same era of people’s lives, the 16:9 ratio might mean another generation, a new hope for freedom of sexuality’s expression, and an era that does not have to bother with labels and rigid classification.

Silence Is a Falling Body may begin with a statement that Jaime is homosexual, looking at how he filmed a statue of a male body and how his camera zoomed in on thighs, buttock, genitals. However, as the film goes on, the scene seems more a tease to the audience than an indication of Jaime’s sexuality: how could you base a verdict on one’s sexual orientation only on footage of a male body? The film answers along the way, providing evidence that it might be more complicated than that. The film depicts and accepts all Jaime’s contradictions, portraying him as humanely as possible.

![ドキュ山ライブ! [DOCU-YAMA LIVE!]](http://www.yidff-live.info/wp-content/themes/yidff-live_2017/images/header_sp_logo1.png)