Yearly Archives: 2015

Children of the Storm

Lav Diaz’s minimalist treatise on the enduring resilience of the Filipino spirit

“We are the storm people. The storm could be the Filipinos’ original Anito (God)… So, yes the storm gives the Filipino a resiliency that’s uniquely Filipino because it’s become a metaphor for restarting, rebuilding, reconstruction, relocation, rebirth… Amid a very corporeal history, there’s the storm, the Filipino’s god of all gods, which has somehow become the great paradoxical equalizer, giving the Filipino a complex logic/illogic cultural discourse; a philosophy founded on the patterns of nature; the meaning of existence is appropriated by nature’s ways.”

The above excerpts are taken from a 2013 interview with Lav Diaz in CinemaScope magazine, where he was asked about the “ubiquity” of storms in the Philippines. After watching his Storm Children: Book One, as part of the 2015 Yamagata International Documentary Film Festival’s Film Criticism Collective Program, this quote instantly came to mind. Diaz’s estimation of this Filipino reality carries a great philosophical weight for the understanding of our psyche – why despite being battered by 20 storms a year, hope still springs eternal. This affinity to the subject matter is perhaps what prompted him to head straight into the most ravaged city of Tacloban three months after Typhoon Haiyan left its destructive path in December 2013. Haiyan, considered to be the strongest typhoon in history, almost defaced an entire city and destroyed livelihood and lives. The tragedy is enormous and the impact on the people who lived to tell the horrors of that onslaught is unspeakable.

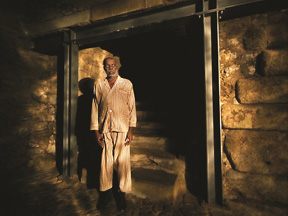

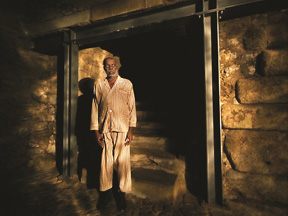

But in Diaz’s documentary, a perfect example of Direct Cinema, the tragedy and poverty that arose from the destruction are never mined to elicit charity or pity. The straightforwardness of the approach is deliberate (the credits would show you that the film is “recorded by”), capturing long static shots of floodwater, debris and the children who frolic and rummage through them, with little editing, letting us soak through images and getting a feel of the place. This approach is in fact trademark Diaz, employing the same style of black and white photography and slow, deliberate pace, which is featured in his better known narrative works.

But the documentation changes pace in the second half. The static shots and long takes are now interspersed with handheld ones. Where in the first half the camera records the events at a distance, Diaz slowly inches closer to his subjects – the children who scavenge this seemingly post-apocalyptic milieu. He briefly allows one character – a boy we see tirelessly fetching water for his family – to have a voice. The boy laments how his older brother gets to complain about him resting while the older brother does not even have the ability to find a job. It is a powerful scene, one that shows Diaz’s understanding of the humanity that still persists amidst the tragedy. It is also one of the scenes where Diaz clearly puts faith in the resiliency of the Filipinos’ spirit: the children seen here embody the courage to soldier on (there is even one scene where a group of young girls sing “Let it Go” from Frozen, a stark contrast to their reality). He also spends considerable time filming two boys digging in a mound of debris. This is Diaz giving us a sense of his own search for meaning – the images reflecting the uncertainty of the first half of the film. He briefly interviews one boy under a ship washed ashore, then follows him to see where his house is. We learn from this brief section how a ship – a towering, uncomfortable visual presence in the film – wrecked a stretch of houses in a single swoop.

Diaz shot Storm Children at the same time he was editing his Locarno-winning Mula sa Kung Ano ang Noon (From What Is Before). And while From What Is Before is set in pre-Martial Law Philippines, both films portray a society that grapples with the reality and brutality of change, whether political or natural. The soundtrack of rushing water, especially in the first half, also recalls the diegetic use of the terrifying waves in From What Is Before. Water in both films serves as a physical force that the characters find themselves having to struggle with – whether it is rushing or roiling, it is an ever-present reality like the reality of the typhoon in Philippine culture.

While Diaz’s eye is focused on the children, in one scene before the final moments he gives a certain humanity to the adults, who are almost entirely absent in the film – a man is shown reconstructing a part of his house, an elderly man passing by stops and helps him. After this show of solidarity, Diaz comes back to the theme of resilience in his final shots. This time, the portrayal has an almost magical tinge. We see groups of children rafting towards two enormous ships, climbing the ladders, jumping with carefree abandon into the sea. The image plays like a loop, and the children have made something impossible – they have turned the symbols of destruction into a playground of innocence and rebirth where the possibility of hope and joy still exists. (Jay Rosas)

Resilience Amidst Rubble

Lav Diaz’s striking monochromatic visuals map the daily endurance of young survivors in the wake of natural disaster

Resilience, radiance, recovery—these are the personal victories of Tacloban’s afflicted youth that Filipino filmmaker Lav Diaz’s radically aestheticised documentary, Storm Children—Book One, unswervingly seeks to illuminate. Chronicled as one of the deadliest tropical storms in Philippine history, Typhoon Yolanda claimed the lives of thousands, leaving only a trail of grief and devastation that lives on in the film’s subjects: young Filipino survivors who, having suffered tremendous trauma, spend their days attempting to re-establish a sense of normalcy in their ruined hometowns. Throughout Storm Children—Book One, Diaz walks with the children in fierce consolation through the wreckage as they seek meaningful ways to cope with their irrevocably altered realities.

Diaz treats his young characters with overwhelming reverence, evidenced in the deliberate physical and emotional space that the camera is careful to keep. Aware that the tumultous emotional process involved in new beginnings—trepidation, adaptation, experimentation, navigating the unfamiliar—has already commenced for the children, Diaz approaches his subjects from a place of quiet, unobtrusive observation, as though his lens is another kid in the village, a loyal compassionate companion who understands the beauty of silence. Diaz does not interfere, offer advice, or coax stories of grief. When a boy crouched on a ledge buries his face in his hands, the camera is static with focus kept purposefully blurry, preventing us from scrutinizing the boy’s features. Diaz’s message is clear: we are here not to pity these children, but to marvel at their endurance.

Meticulous aesthetic attention is paid to framing and mise-en-scene. The striking visuals and diegetic sound choices intentionally break any concept of the documentary as an exploitation of poverty. Crisp, stunning black-and-white visuals render the wreckage beautiful, and every unhurried shot feels laden with meaning. As kids splash gleefully in flooded streets at the film’s start, the monochromatic colouring inhibits our ability to gauge the dirtiness of the water, likely teeming with car oil, street dirt, rodents and litter, as if to say, this is not the point: the children are the point.

Diaz’s deep repugnance of emotional exploitation is evident in his preference to show, rather than say. His reactions remain neutral, and he makes no attempt to coax words from the children. “That’s my house,” a boy tells Diaz, pointing to a tent. “But I’m not ashamed of it.” The director’s response is measured: “No, of course you shouldn’t be.” Ethical questions about poverty and activism simmer beneath the surface of a brief scene in Leyte, when white tourists stop to take photographs with a group of grubby children in the remnants of a doorway before vanishing into the distance. Midway through the film, we follow a lone young boy who works as a water carrier. Only after a significant time has passed does Diaz allow a single close up, his lens staying far enough away as to observe without voyeurism. The camera rests on the boy’s face, innocent and unblemished, eyes bright and curious, before Diaz abruptly cuts away to a new scene, a new story. His dedication to maintaining respect for the children is unwavering: they are not victims, they are survivors.

Diaz’s celebration of the resilience of the storm children is powerfully reinforced in the documentary’s final moments, when the camera observes Leyte’s children clambering deftly up a ship named ‘David Legazpi’ and jumping gleefully into the ocean. In that instant, we poignantly recall one of the few snippets of dialogue that Diaz allows us to hear, wherein a teen boy points off-camera and says: “That’s the ship that swept our houses. The David Legazpi.” The ship that wiped out half of the community during the typhoon. The beauty of the irony is not lost on Diaz, who cuts the sound. Silence rings in our ears as the children frolic in slow motion beneath the ship’s printed name, and we realize that the ship that brought the children so much pain, grief, and loss, is the very entity that enables them to recover the playful innocence of their youth. Each time a storm child climbs the Legazpi’s ladder, jumping from the steep hull into the depths of the water below, they resurface anew: brighter, steadier, and ready to take their next plunge. (Melissa Legarda Alcantara)

コミュニケーションツールとしてのシュルーム・リチュアル

一度シュルームを服用すると、人格が変わるという。それも、数十年にわたる影響力だ。「シュルーム」とは、欧米において幻覚性キノコを指す隠語のことで、日本では長年、マジックマッシュルームの名でその危険性や魅惑が謳われてきた。

メキシコ先住民マサテコ族のシャーマンとして幻覚性キノコを用いた精神療法を長年行い、その名を世界に轟かせたマリア・サビーナについてのドキュメンタリーを観た。監督は今年の山形国際ドキュメンタリー映画祭のインターナショナル・コンペティション部門審査員を務める、ニコラス・エチェバリアだ。『マリア・サビーナ 女の霊』は1979年に完成された彼の初めての長編ドキュメンタリーである。世界初の民族菌類学映像資料として、世界中の先住民学者やシャーマニズムの研究者、ヒッピー達に今も受け継がれる同作品は、16ミリの手持ちカメラでマリア・サビーナの生活ぶりや彼女が儀式を行う光景の一部始終を記録している。

本作は冒頭のテロップによる解説、マリア・サビーナの一人称で読み上げられるナレーション、そして被写体を捉える映像によって構成される。まるで詩を読んでいるかのようなナレーションは、サビーナとアメリカの菌類研究家ゴードン・ワッソンの対談録を基にして作られている。スペイン語のオリジナル版ではナレーションはあえて男性が担当しているのだが、英語版ではあいにく女性の声となっていた。それでも、宗教的職能者の持つ男性的な逞しさを言葉の中から感じることができる。劇中、 朝靄のなかで朝日が山々を照らす美しいロングショットが幾度となく挿入される。観ているだけで開放感に浸れる清々しいショットだが、どこかサウダージをも感じさせる。

身体と心は繋がっている。だから身体を病んでいるときは心を癒し、心を病んでいるときは身体を癒してあげればよいのだ、と聖なるキノコの母は云う。大きく腫れ上げた両足をひきずりながらマサテコ族の女性が彼女を訪れ、ついに儀式が始まる 。明くる朝、彼女は一人で山に行きキノコを収穫する。そして午後は、採ったばかりのキノコを作法に従って炙り、指先を使って細かく裂く。日が沈みきってから、闇と静寂に包まれた部屋に蝋燭を灯し、病に苦しむ訪問者と彼女を祟る仲間たち、そして親類を交えてキノコを食す。女性シャーマンは彼女の足を優しく摩りながら、救済を求める歌を唱え続ける。心身の毒素は嘔吐する行為によって吐き出されると信じるこの儀式では、病人が嘔吐できない場合、マリア・サビーナが自身の肉体を使って嘔吐を代行するという。病人を精神的苦痛から解放するシュルーム儀式は、どこか、彼女自身が誰かを癒すことで自ら癒される光景のように見えた。

マリア・サビーナは村を訪れる人に見返りを求めずただひたすら儀式を行っていた。彼女にとって、儀式は神との交流の手段であるだけでなく、彼女自身が村社会のなかで他人から必要とされていることを確信できる時間でもある。心身を病んだ人間を救おうとする彼女の行為は、手段こそ我々には馴染みのないものかもしれないが、人道にかなった行為に代わりはない。貧しい家に生まれ、餓えをしのぐために参加した宗教儀式で出会ったキノコは、彼女にとって信仰と快楽のツールのみならず、貧しいシャーマンとマサテコ族、あるいは人間と人間を繋げるメディアとして機能しているのかもしれない。撮影当時で推定80歳、鋭い目力に反して抜けた歯が年齢を感じさせる、慈愛深きマリア・サビーナには、彼女を必要としてくれる人間が是非とも必要だったのだ。(青山エイミー)

《闇と光の儀式―マリア・サビーナ 女の霊》

映画を観ることは、光を見つめることであり、闇を見つめることだ。闇を見つめることは、同時に陶酔することでもある。メキシコの山奥に、マリア・サビーナという、光を見つめ、闇を見つめ、陶酔する女性がいる。彼女は、キノコや薬草を使って幻覚作用をもたらしながら、伝統的な治療をするシャーマンの女性である。貧しい環境のなかで、父を亡くし、母から自立し、夫に先立たれて未亡人となったマリア・サビーナは、幼い頃から身近に自生していたキノコを摂取することで、神と対話できることを知る。

幻覚作用のあるキノコを摂取しながら行われる儀式は、夜のみ行われる。信じること、信じるものだけが癒される、目をつむるのではない、無限の闇を見つめることだと語るマリア・サビーナは、夜にしかキノコを摂取してはいけないと何度も語る。陶酔は、昼間には起こりえない。闇という余白のもと、改めて目を凝らすことで、色彩は強くなり、音は鋭く響き、光は輝き、私たちはある種の緊張状態に置かれる。夜は、そして闇は、陶酔において偉大なのだ。日中に何もやることなくぼんやりと過ごしているひと、或いは生活のためにやりたくないことしている人にだって、夜になったら陶酔する権利があるのだと囁かれているかのようだ。

しかし私たち観客に許されるのは、映画を見つめることだけである。私たちはキノコを摂取しながら映画を観るわけではなく、暗闇に座りスクリーンの光を見ることのみ許されている。幻想的に映し出されるロウソクや、治療の儀式をしながら彼女らが身体をゆったりと左右に動かす仕草、マリア・サビーナの静かな歌い声、そういった映画内にちりばめられた陶酔させる力のある映像は、暗闇に身を置いて見つめるという行為に準じる私たちにも多少の陶酔効果を及ぼすかもしれない。しかし、いくら触れたくても、私たちは映画に触れることはできない。もちろんその場に行けるわけでもない。この映画の魅力は、作品内に「見つめる存在」が映り込むことで、本来だと受動的に見つめることしか出来ない観客が、映画に向かってぐっと親密に近づくことが可能な点である。見つめる存在とは、つまりその場所まで儀式を見学しに来た、焦点のあたることがない観客たちのことだ。マリア・サビーナは、1957年にLIFE誌でキノコ研究家のゴードン・ワッソンに紹介されたことで一躍有名になり、多くの人が彼女の元を訪れるようになった。この映画のなかでは、彼ら観客がまるで外部の異質なものであるかのように、画面の端に少しだけ映されている。暗闇に紛れ壁側に佇む彼らの横顔や足は、外から見つめることしか出来ない存在として、暗闇に座って映画を見つめる私たちと重なり合う。そして私たちは、彼らを通すことによって、見つめるということ、闇に佇むということ、そして光を見つめることの圧倒的な無力さと同時に、光のイメージと音の持つ力強さを感じることができるのだ。(石原海)

戦争のなかにも平和はある――『鉱』

劇場に轟音が響きわたる。スクリーンにまで伝わるかのような機械の振動。暗く湿った空間の向こうで、労働者たちが身に着けるヘッドライトの光が絶え間なく揺れ動いている。ここはボスニアの炭鉱、地下300mの異世界だ。つねに事故の危険と隣り合わせにある坑内で、カメラは動じることなく坑夫たちの肉体を、掘削機械の運動を、いずれも淡々とした速度で捉えていく。狭く足場の悪い状況であるにもかかわらず、監督の小田香――タル・ベーラがサラエボに設立した育成プログラムに学んだ――による撮影はけっして取り乱すことがない。卓越した長回しと固定ショットの多用によって、ここではきわめて静謐な雰囲気が醸成されているのである。

それは、しばしば劇映画などで描かれる鉱山労働のイメージとはどこか異なっている。現実に炭鉱という言葉を聞くと、私たちは過酷な労働環境を想像してしまうに違いない。たしかにそれはまぎれもない事実であり、本作にもそのような実態は少なからず表出している。たとえば落盤事故で大怪我を負った仲間の話をする坑夫たちは、ふとカメラの方を向いて尋ねるだろう。「監督さん、いったいこれは誰の責任なんだ?」「いつになったら問題は改善されるんだ?」

だが、それにもかかわらず本作は社会問題を扱った映画ではない。あきらかに監督の興味はまったく別の対象に向かっているからだ。その温かい視線の先にあるのは、何よりも肉体労働の本質的な美しさであり、機械の純粋な運動性である。様々な騒音のなかに認められる「音楽」であると言ってもいいかもしれない。いわば本作は、きわめて純粋な探究心によって、坑内における激しい戦いの内奥から、一瞬の静寂を「掘り出そうと」試みる映画なのである。

この作品につけられたタイトルは「鉱」(あらがね)。あるいは、それを「荒金」と記してみるのもいいだろう。鋭く響き渡るつるはしの音や、ぼそぼそとして聞き取れない坑夫たちの話し声、無骨で怪物的な機械のフォルム。それらは、まだ精錬されておらず荒々しい鉱石の質感にも似ている。その石が監督の手によって編集され、劇場のスクリーンに映し出されるとき、私たちはそこに磨き上げられた金属が放つ、幾何学的で美しい輝きを見出すに違いない。映画によって炭鉱を描くということが、これほどまでに映画的であるという事実に、私たちはいま、はじめて気がついたのかもしれない。(村松泰聖)

The Cases of Ventura and the Pearl Button

Despite totally opposite approaches, the latest films of Patrizio Guzmán and Pedro Costa are masterpieces in portraying those who have been forgotten.

Patrizio Guzmán’s The Pearl Button and Pedro Costa’s Horse Money were screened back to back at Yamagata International Documentary Film Festival. It was a great opportunity and pleasure not only seeing how stunning and captivating the two films’ visuals are, but looking deeper into how the directors convey a similar message with absolutely different approaches.

Both films are about politically forgotten ones: native peoples who faced genocide from colonization and victims of Pinochet’s regime in Chile, and Cape Verdeans who have to live miserably in a metaphorical prison of Portugal before and after the Carnation Revolution. The conditions of the two filmmakers are extremely distinct: most Chilean filmmakers and the world join Guzmán in criticizing the American-supported military government, while Costa is almost the only active Portuguese filmmaker continuously criticizing the revolution that has been generally named democratic. The approaches of the two films are also quite different. In The Pearl Button, the water of Western Patagonia is cosmically presented both in content and form as something that transcends boundaries, in contrast with the colossal darkness and fear that, in Horse Money, Ventura with his fellow Cape Verdeans cannot escape and in which they exist like ghosts.

“We are all streams from one water,” Guzmán says, quoting Chilean poet Raul Zurita. He uses the phrase to connect the dots of history, from the 3000-year-old quartz with a drop of water inside, to water nomads who made their living in the aquatic labyrinth, to the unique geography which created a geographical sense of Chile as islands with mysteries and also created the conditions for secret concentration camps, to the pearl button – an unexpected legacy of the colonizers which powerfully connects the whole picture and provides the film’s title – that confirms the existence of the vast graves under the sea. The film blends political statements with science by means of La Silla Observatory, the space observation base located in the Atacama Desert which detected faraway planets that may contain water in various forms. Water becomes alive in Guzmán’s realm. It contains the memories and voices of those who died, were forgotten, or are buried. Voices and memories here constantly exist, they evaporate and could become rain anywhere else, including outer space. This is an enormously fresh take in comparison with average political films. Guzmán successfully convinces us with his unique narrative, triggers our emotions with powerful images such as space, comets and the massive destruction of supernova which reached earthly audiences in the same time as the death of Salvador Allende.

While Guzmán’s water represents the perpetuality of time, in Horse Money, Costa’s architecture combines with dark shadows to represent its restrictions. The collective pain of Ventura and the Cape Verdeans is astonishingly presented with bizarre static shots, editing and screenwriting that creates a special realm with its own code of time and space (he is nineteen years old but already retired from labor), all information scattered everywhere. Dimensions are completely twisted in Ventura’s realm; history and memories visually haunt him in the form of ghosts from the past and slowly degrade his physical conditions. The film is constructed upon Costa and Ventura’s memories of April 25th 1974, when the director was a youth yelling revolutionary songs. Thirty years later he found out another parallel story – while he was singing with joy, Ventura and his compatriots were hiding from immigration officials with overwhelming fear. Spirituality here is devastating, memories are disastrous, and voices are destructive enough to turn every living soul into another wandering ghost. Ventura is Costa’s friend in real life, but in Horse Money we cannot confirm his human status, which means that somehow he is a ghost who has been haunted by the other ghosts; we cannot even confirm the status of the exit seen at the end of the film.

The Pearl Button presents a crystal-clear sign of progression and hope that these forgotten voices and memories will be eternally heard through the entire history of planet Earth in times to come. On the contrary, there are strong signs of regression, agony and hopelessness in Horse Money. This prison was built upon forgetting, and Costa’s only suggestion of the way out is: try as hard as you can to forget that we are forgotten. (Chayanin Tiangpitayagorn)

真実の「自分語り」――『私の非情な家』

現代とは「自分語り」の時代であるといえるだろう。たとえばツイッターやブログを通して、私たちは日々の出来事や自身の生い立ち、怒りや悲しみを自由に表現している。もはや特別の技能や権威がなくても、個人の経験を社会に向けて発信することができる時代なのである。けれども、これだけ「自分語り」が氾濫する環境に身を置いているせいで、私たちは重要なことを忘れてしまっているような気がしてならない。それは「自分語り」の本質的な難しさだ。経験を世界に向けて物語るということは、人が考えている以上に困難な行為なのである。社会には様々な理由によって自身の身に起きた出来事を語ることのできない人々が存在している。韓国人の「イルカ」もその一人だ。

「私は洗脳されていました」――映画の冒頭で発せられる彼女の言葉が、私たちの胸に強い衝撃を与える。「イルカ」dolphinという仮名によってスクリーンに登場する彼女は、かつて父親から性的暴行を受けていた。はじめ、父親はそれをスキンシップと説明していたという。だがある日、彼女は父の行為が許されない犯罪であった事実に気がつく。家を飛び出し大学を辞した彼女は、被害者支援団体とともに父親を告訴。それは、なおも父と暮らしている二人の妹を守るための決断でもあった。

裁判となれば、イルカは自身の被害を詳細に物語らなければならない。心に大きな傷跡を残している彼女にとって、それは重く辛い行為である。にもかかわらず、法廷の証言台に立つ彼女の声は力強く、その決意は固い。むしろ周囲の人間のほうが、彼女の過去に立ち入ることに対して二の足を踏んでいる事態に私たちは気がつくだろう。たとえば、暴行されていたことを彼女が最初に相談したはずのボーイフレンドは、裁判記録が将来のキャリアに差し支えることを懸念し、みずから証言台に立つことに対して乗り気ではない。あるいはまた、初対面の占い師にまで自身の体験を話して聞かせようとするイルカを、カメラマンは慌てて制止するだろう。そんなとき、彼女は強く反発するのだ。なぜならば、彼女にとって「自分語り」をするという行為こそが、家族を救い、自身の未来を切り開くための唯一の手段であるからにほかならない。

経験を物語るということ。そこには語る人間の意志や覚悟がともなわれている。父が嘘で塗り固めた虚構の物語と戦うために、証言台の彼女は全身全霊をこめて声を発するだろう。ある信念によって発せられる「自分語り」の力が、『私の非情な家』という作品にはあふれているのである。(村松泰聖)

《車窓風景とドキュメンタリーにおけるドラマ性―ドリームキャッチャー》

シカゴで性暴力を受けた女性を支援する「ドリームキャッチャー・ファウンデーション」というボランティア団体がある。そこで働くブレンダという女性を中心に映画は展開していく。かつては彼女自身が売春をしており、他の女の子を売春に誘ってポン引きに渡したり、薬物中毒だったり、性暴力の被害にあっていたというバッググラウンドを持つ女性だ。しかし同時に、そのような過去があったようには見えないくらい陽気で、劇中では激しい洪水のように、よく笑いよく泣き、よく歌って踊っている。夜になると、彼女は売春婦が多く立っている道や危険とされている地区まで車を流して、実際に売春を生業とする女性らと対話をする。そしてこの場から足を洗いたい、しかし一歩が踏み出せないでいるひとたちを助けるために全力を尽くす。

映画のなかで、車内から撮影された風景の映像や、ブレンダ自身が運転しているシーンが何度か登場する。それはいわゆるアメリカの車窓風景に過ぎないのだが、同時に犯罪映画的でもある。ゆるやかな速度で町を徘徊する映像は、まるで彼女自身が女を買おうと物色しながら町を車でゆっくり流しているかのような、少し気味が悪いものとなっている。この幾度か挿入される車窓風景の映像や、車の動きによって、ドキュメンタリーであると同時に、ドラマ的な演出構造が立ち上がる。

ブレンダはすでに数多くの悩める女性を抱えているが、ひとりひとりに向き合い、自分の経験を交えながら、真摯に力強く女性を励ます。ではなぜ、有給でもない「ドリームキャッチャー」の仕事にここまで没頭するのか。それは、恐らく彼女自身が物語ることを誰よりも必要としているからだろう。売春をして苦しんでいる女性と会うことを通して、彼女はかつて自分が行っていたことに類似した過去を見る。過去を忘れようとすることは、自分を遠回しに否定することだ。だから、過去の痛みを受け入れて語り続けねばならない。

映画は数時間だが、映画が終わったあとでも自分のかつて手にした痛みは消えることがなく、主題は永遠に繰り返される。同じ歌を何度も歌いたいように、同じ話は何度もしたいし、同じことだって何度も書きたいし、私たちは同じことで何度も怒ったり、悲しんだりしてしまう。映画のなかで車が円状に町を巡回することは、ブレンダの過去が持つ重みの、永遠に循環される終わりのなさを表しているのだ。一度でも悲しみが起きてしまったら、それは取り返しのつかない記憶として自分の身体に蓄積されてしまう。その蓄積されたものを消すことはほとんど不可能だが、痛みとともに、同じことを繰り返しながらゆったりと変化して生きることを、この映画は肯定しているのだろう。(石原海)

「女性達だけの神秘的な空間」

映画監督が自らの家族にカメラを向ける目的は、なんだろう。家庭というプライベートな空間を外部の人にみせることで特殊な家庭環境を理解してもらうため? それとも、愛する家族との時間を記録して保存したいという願いから? 『女たち、彼女たち』の監督、フリア・ペッシェの場合、答えは「どちらも」だ。女性だけの家庭内で繰り広げられる会話は、痛々しいほどに現実的である。しかし、外の世界から隔たれた彼女たちだけの空間は、時としてはっと息をのむほどに神秘的なのである。

ひんやりと冷たそうな老婆の足をマッサージする場面から始まるこの作品は、アルゼンチンの郊外にある9人の女性たちが暮らす住まいに焦点を当てる。監督の家族だ。死が迫っているのは、大叔母。その隣には、こちらも介護を必要とする祖母。交代に介護を手伝うのは、若い従姉妹たち。母と叔母は、多忙の身ながら老人ホームを探すことに頭を悩ませている。女性たちは、助け合ったり、口論したり、なぐさめあうことを繰り返しながら生活している。男性はいない。気配すら、ない。世代を超えた9人の女性たちが支え合いながら暮らす光景を見ていると、どこか「おんなの小宇宙」に迷い込んでしまったような錯覚に陥る。一家がピクニックに行くシーンがある。草むらで水着姿の女性たちが、隣の太腿に頭を置いて円を描くように横になり、自然の音に耳をすませる。楽園を想起させる神秘的なシーンだ。

撮影は全て手持ちで行われ、カメラは家じゅうの女性たちをどこまでも追いかける。入浴シーンも何度もある。繰り返される日々の営みに重きを置いているからこそ、これらの場面も隠すことなく映し出されるのだ。老婆と妊婦の入浴場面のコントラストは、計算し尽くされたこの作品の凄さを物語り、この作品で特筆すべきは、死と生を並列させることにある。死にゆくおんなの姿、それを支えるおんなの姿、そして新しい命を宿ったおんなの姿。

自宅出産を記録したクライマックスは、 監督が妊婦の実姉であるゆえに可能である。繊細な暖色の間接照明が、必要な情報だけに光を当て、「オーム」とゆっくりマントラを唱えながら、助産婦は妊婦の緊張をほぐす。儚くて逞しい母体と、そこから切り離されるべく生まれてくる新しい生命を目の当たりにする、奇跡の体験だった。「これは、私の子なのよね」と、産み落とした直後の母親は確かめるように助産婦に訊く。それに対する助産婦の答えは、生命の循環を喚起させ、胸が熱くなる。(青山エイミー)

Silent All These Years

A universal truth in a personal documentary about deaf parents and the silence that binds

Being enrolled in a “special education” school for most of my elementary and high school years, I grew up with deaf and mute kids around me. Although we did not have a special course designed to teach us sign language, we picked up some of the basic gestures from inevitable interactions with them. With this disability, the deaf and mute kids obviously had to band on their own, drifting in their own silent bubble, while the rest of us with the ability to talk got embroiled in our own chaotic noise. It was easy to understand the difficulty of raising a child with a hearing or speaking defect, but I never imagined it the other way around – where the parents are the ones with the disability. Watching Lee-kil Bora’s personal documentary Glittering Hands, which screened as part of the New Asian Currents section of the 2015 Yamagata International Documentary Film Festival, I remembered having one schoolmate who had deaf parents and it was only then that it occurred to me how oblivious I was to this facet of dealing with disability.

Essentially, Lee-kil’s film resembles and has the feel of a personal home video with various VHS clips interspersed with interviews. The first half of the documentary traces the history of the filmmaker’s deaf parents, quickly establishing their story – how they met, got married and had children. The film’s other half focuses on Lee-kil’s story and that of her brother, as they narrate their experiences growing up with their parents. These stories show that the burden is shared — it is heartbreaking to hear both the filmmaker and her brother echo the same feeling: “the disability label was on me” — and that understanding and patience was the currency that allowed them to navigate the silence between their two disparate worlds (“words couldn’t capture, only silence could”). Lee-kil shatters the clichéd concept of a dysfunctional family, a subject matter so relentlessly overplayed in narrative dramas.

While the director interviews her parents, she limits her participation and allows them to openly engage in conversation about how difficult it was to raise children and their plans to buy a country house, capturing both recollection and insight, personal history and the nuances in their relationship. In sign language, they attempt to recreate memories of a past, without being regretful, and this same language, despite its codes and symbols, assures us that something that is innately genuine cannot be lost in translation. The parents’ exchanges are filled with light and funny moments, conveying their humanity and authenticity, while our awareness of their disability vanishes in the flurry of hand gestures and intermittent sounds that come out of their animated conversations.

The director uses a collection of snippets from an archive of home videos, presumably taken by her parents (especially the one showing her growing up). This mode of recording already hints at the importance of imagery and visual communication, not just as a means of understanding in a world governed by silence, but also as an act of memory-making and preservation. Lee-kil’s directorial touches exhibit a keen understanding of the human condition in the way she balances what could have been a heavily emotional story with humor. Although during the Q&A for the film, Lee-kil said that she intended her film as a platform for awareness and advocacy, what is really striking and compelling is that the film becomes an act of self-rediscovery and introspection, embodying the possibility of learning a newer, more holistic truth through the medium of film. And this is where Glittering Hands excels as a piece of cinema – Lee-kil has made something universal out of the very personal. (Jay Rosas)

Secrets of the Sea

Documentarist Patricio Guzmán finds Chile’s geography, history, and loss encompassed in the memory of its oceans

Chilean filmmaker Patricio Guzmán’s critically acclaimed documentary, Nostalgia for the Light, wove together poignant meditations on astronomy, political repression and lost potential using the geography of the Atacama Desert, reputed to be the most arid region on earth. Guzmán returns to these lofty subjects in The Pearl Button, an equally profound scrutinization of Chile’s colonial brutality towards its people alongside humanity’s relationship to the universe, this time employing the element of water.

Early in the film, Guzmán laments that despite having one of the longest coastlines on earth, contemporary Chile lost a significant part of its identity by failing to acknowledge its oceans. Using the archipelagic waters of Patagonia as an entry channel, Guzmán artfully plumbs the depths of Chile’s dark secrets, his poetical ruminations flowing effortlessly from the cosmic (such as the dazzling galaxies observed by colossal radio satellites in Atacama) to the man-made (ancient wooden canoes and spine-chilling relics of mass genocide).

Guzmán’s proposal that water contains the history of humanity might appear tenuous, but eventually, all the seemingly disparate subjects of the film are meaningfully bridged together through a button discovered at the bottom of the ocean. His deeply nostalgic – but never romanticised – recollections of Patagonia’s native water nomads and their genocide at the hands of cruel foreign settlers and missionaries are juxtaposed with a sobering re-enactment of the barbaric tragedies that occurred under the Pinochet rule, when political prisoners of the 1970s were slaughtered by the thousand and dumped into the sea. Later, when we learn of Jemmy Button, the first native to be brought to ‘civilisation’ (and the inspiration for the film’s title) for the price of a pearl button, Guzmán confronts us with the knowledge that the native underwent a traumatic historical experience, “travelling from the Stone Age to the Industrial Revolution” in a heartbeat.

Epiphanic moments abound, both philosophical and visual. Guzmán’s humanist, deeply provocative narration is complemented by cinematographer Katell Djian’s high-res imagery. In one second we transition from micro to macro: from a universe of pollen and dust swirling within a single drop of water to staggering footage of glittering space nebulae that fill the universe above us. Throughout the film, conventional beauty is interspersed with more jarring elements. When a vocal musician “sings” the music of water, his glottal drone is otherworldly, just as uncanny and ancient-sounding as the nearly extinct language of Kawésqar, spoken in the film at Guzmán’s request by the handful of surviving descendants. Martin Gusinde’s black-and-white portraits of masked natives, their naked bodies adorned with intricate patterns and lines, melt supernaturally into glorious vistas of the cosmos, a transition which shows that for all our technological advancement, modern humanity has no more understanding of the universe than what the ancient Kawésqars could intuit.

The luminous rhythm and power of The Pearl Button stem from Guzmán’s sensitivity towards the synchronicity of the universe, deepened by his anger over Chile’s losses, whether the loss of human lives, of indigenous knowledge, or of its relationship to its seas. But just as the Kawésqar water nomads believed that all things in the universe are alive and intertwined, so too does Guzmán discover that traces of Chile’s (and humanity’s) history continue to live on in the cemetery of the ocean, reminding us that in our universe, everything is connected, and nothing truly lost. (Melissa Legarda Alcantara)

映画は、だれのもの

「ドキュメンタリーは、社会を映し出す鏡である」という言葉をよく目にする。

「ドキュメンタリーに見る現代台湾の光と影 映像は語る」は、1990年代の台湾ドキュメンタリーを通して、社会の変容を、様々な環境に身を置く個人の生活や想いを映しだす鏡の集合体といえるかもしれない。

今回とりあげる『あの頃、この時』楊力洲(ヤン・リーチョウ)監督作品は、台湾の映画賞「金馬賞」の50周年を記念して製作された。映画史から戦後台湾の歩みを描いたドキュメンタリー作品だ。映画の歴史から戦後の台湾社会をみつめている。

金馬賞は、蒋介石の誕生日を記念したもので、当初は台湾総統府の意向にそったものだった。民間に委ねられてからは、社会の動向の影響を受けて、変化していく様を、映画の映像を散りばめ、走馬灯のように描いていく。映画史を語るとともに、監督や俳優といった制作者や映画の観客の個人のインタビューを、随所にはさみ込む構成になっている。

「あなたにとって、映画とは何ですか」「どれだけ愛していますか」という監督の問いに、それぞれが、思いのたけを告白しているかのように感じられた。

インタビューに答えた一人の女性は、地方出身で、台湾が農業社会から工業化への変換期に、長女として家計を支えるため工員となった。十代半ばから働き始めた彼女にとっての楽しみは、文芸恋愛映画をみることだった。

上映後のトークショーで、監督は映画にはなかったエピソードを明かした。彼女に

「印象に残っている恋愛映画はなんですか」と尋ねると、『一片の雲』とタイトルをあげ、主題歌を歌ってくれた。一番を歌い終えると泣きだしたのを見て、文芸恋愛映画を軽んじていた自分を恥じたという。

台湾では、長女に生まれれば、自分を犠牲にして家族を支えるのが当たり前だった。そんな一人の女性にとって、スターが演じる夢のような恋愛を描いた映画は、心のよりどころだった。

映画は人の記憶に結びついている。映画は、現実を生きる観客と関わりあうことで、本当の完成をみるのかもしれない。

台湾映画が低迷した時期、外国の資本で製作するという活路を見いだすが、作り手たちは、売上は外国にいってしまう。これでは、工員と同じではないかと自問する。模索のすえ、現実社会への理解が映画を生むという真理にいきついた時、「私たちのことを描く、わたしたちの映画」となったのかもない。

日本でもヒットした『海角七号 君想う、国境の南』の主人公について「夢に挫折した私たちと同じ平凡な人間」と観客がつぶやいたのが印象に残った。

映画の中に、自分達の姿をみつけて受け入れる。映画は、わたしたちに寄りそう、親しい友人のような存在なのかもしれない。(島咲 山形市在住)

![ドキュ山ライブ! [DOCU-YAMA LIVE!]](http://www.yidff-live.info/wp-content/themes/yidff-live_2017/images/header_sp_logo1.png)