The Yamagata Film Criticism Workshop will take place for the forth time during YIDFF 2019. This project encourages thoughtful writing on and discussion of cinema, while offering aspiring film critics the chance to immerse themselves in the lively atmosphere of a film festival.

A Non-Place Moving Train

On No Data Plan, directed by Miko Revereza. Philippines/USA, 2018. Presented at YIDFF 2019 in New Asian Currents.

by Elise Shick

When I first saw Miko Revereza’s No Data Plan (2019), it reminded me of Jonas Mekas’s On My Way to Fujiyama, I Saw… (1996). Traveling from one place to another, the director/narrator in each film captures landscapes from the point of view of a moving train by using a handheld camera. However, there is a clear difference between these two films: Mekas’s film emphasizes the ephemerality of how the narrator gazes at the landscape, whereas Revereza shows that time is expandable, as the landscape and the narrator constantly exchange gazes during his three-day journey from Los Angeles to New York.

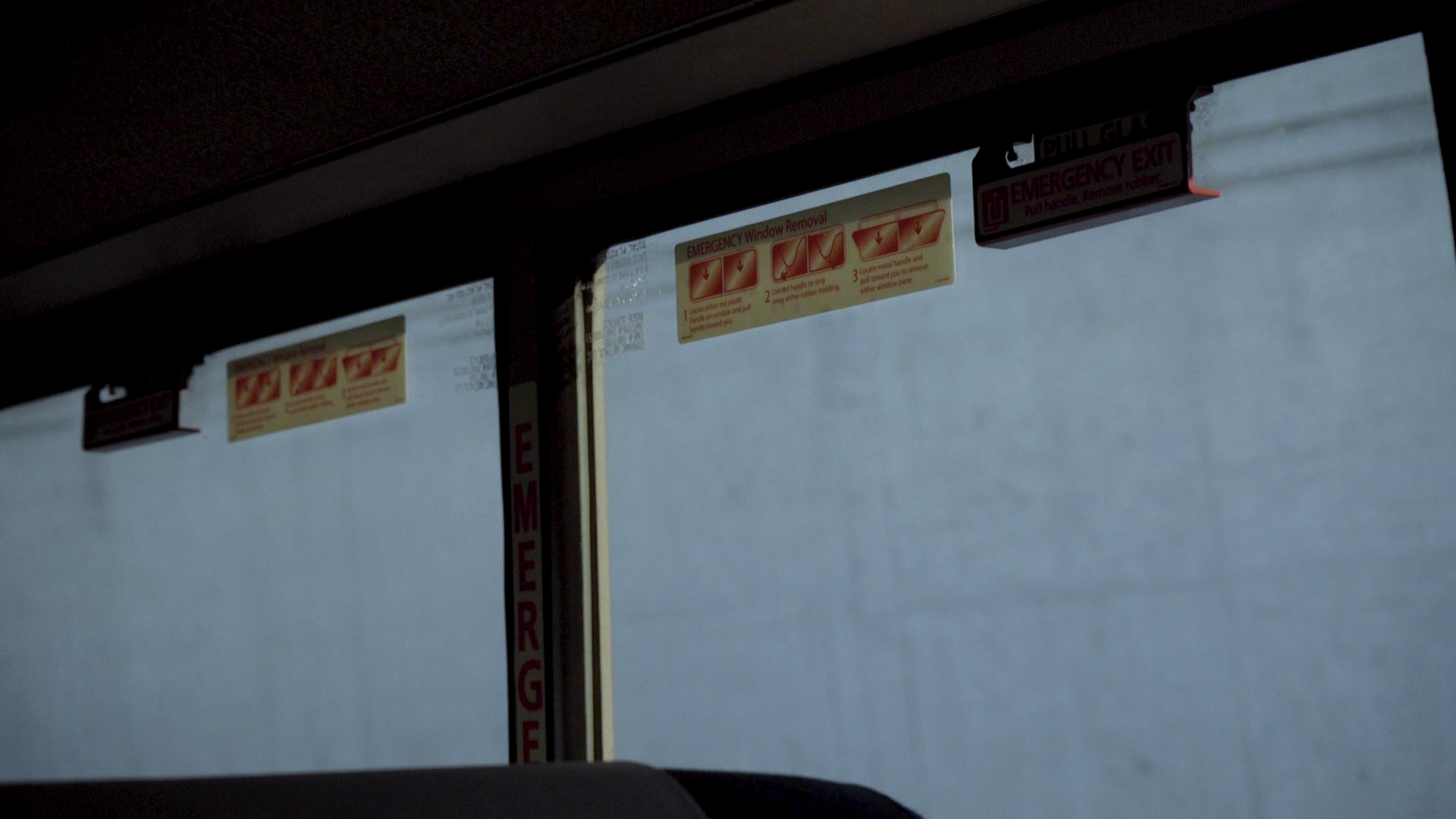

Time slows down as we accompany the filmmaker from the crowded station onto the train. The noise from the surroundings subsides as the text of the narrator’s internal monologue appears superimposed on the images of moving landscape. We see him reflected in the window, holding a camera, aiming at the landscape outside the train, while in his written text he contemplates his existence and the anxieties of being an undocumented person in ICE-age America. Revereza cuts between traveling shots of the landscape and static shots of the cabin seats. As I watch this juxtaposition, I undergo the same experience as the narrator: sitting in a chair and looking at the moving images in front of me while allowing myself to be a stateless, fluid figure who moves between my own consciousness and the film.

The relationship between time and space established by No Data Plan attributes a non-place quality to the train cabin that changes the perception of time and allows self-interrogation. Revereza abolishes past and present as he combines, within the space of the cabin, conversations with his mother, the pain he experiences as a paperless person in the United States, and the recurring dream of being stuck in the Manila airport. The train cabin is not a place of belonging for the narrator and the other passengers. It has a malleable quality. Anonymous passengers board and get off, while the space allows the enactment of their imaginations and memories. As the train moves forward, the narrator becomes increasingly displaced. The sight of unfamiliar places and landscapes reaffirms his stateless status. Strangely, these moving images projected on the screen make me wonder why I, who hold a legitimate citizenship, can still resonate with this sense of displacement during the concentrated 70 minutes of the film.

![ドキュ山ライブ! [DOCU-YAMA LIVE!]](http://www.yidff-live.info/wp-content/themes/yidff-live_2017/images/header_sp_logo1.png)