In the postwar era, there were many modes of documentary, both in terms of production modes and aesthetics. However, the independent, politically engaged, and formally inventive cinema on the left attracted the most attention, and within that the collective mode epitomized by Ogawa Productions was particularly prestigious. It remains deeply valued today, despite the fact that it essentially died out with the demise of the student movement in the 1970s. As I suggested in a previous musing, Living on the River Agano (Aga ni ikiru, 1992) was something of a last gasp of the politically engaged collective documentary.

A new trend took hold around that time, one that was predicated on the emergence of video. Of course, video had been around for a long time. However, by the 1990s the cameras became smaller and cheaper, bringing quality capture within reach of poor independent filmmakers. Perhaps even more importantly, the clunky apparatus needed for video editing gave way to non-linear editing systems on the new personal computers. This registered at the Yamagata International Documentary Film Festival in 1995, when Avid set up a table at the main venue to demonstrate its software to the visiting filmmakers. Adobe Premiere was new as well, and things really changed in 1999 when Apple released its prosumer Final Cut.

With camcorders and desktop editing, a new generation of independents arrived. Many of the new directors were young, penniless, but computer-literate. While the first independent deployments of the new video technology in neighboring Taiwan and Korea were connected to group production and political activism, the young directors in Japan tended to focus on the personal. It’s telling that it has often been called the “private film.” It soon constituted a whole new genre in Japanese documentary, one which sank its roots in the earlier autobiographical films of Hara Kazuo and Suzuki Shiroyasu.

However, this “private film” emerged from the ruins of movement politics. Conceptions of progressive politics in the film world fell into a kind of stasis in the 1970s, when the student movement boiled down, when the vanguard of the Red Army exposed a corruption within the Left by killing its own, when the oil shock hit hard, when the advances of third world and feminist filmmaking and theory were passed by, when Narita airport was completed. Stuck with a conception of the political defined decades in the past, young filmmakers became quick to dismiss any affiliation with it. Their practice of the private was a retreat.

Now this emergence of a new autobiographical documentary was a global phenomenon because the technology was hitting everywhere at once. However, as Susan Hayward has pointed out, one of the fascinations of film history is that, while the technology of cinema is globally homogenous, its uses are radically heterogeneous; in other words, everyone was using camcorders, but in very different ways. Yamagata International Documentary Film Festival took note of the shift and invited Michael Renov, one of the top scholars of documentary, to contribute an article to its journal. Entitled, “New Subjectivities: Documentary and Self-Representation in the Post-Verité Age,” it came out in Documentary Box 7 in the summer of 1995. Renov named the new autobiography the essayistic, and it was substantially defined by approaches that used the self as a way to approach the world. This is to say, documentary was discovering a new politicality. Renov wrote,

The work to which I refer may rework memory or make manifesto-like pronouncements; almost inevitably a self, typically a deeply social self, is being constructed in the process. But what makes this “new subjectivity” new? Perhaps the answer lies in part in the extent to which current documentary self-inscription enacts identities – fluid, multiple, even contradictory – while remaining fully embroiled with public discourses. In this way, the work escapes charges of solipsism or self-absorption.

What was striking about the Japanese iteration, however, was its reticence to connect the self of the filmmaker to the world. And even the directors that made the jump were debilitated by their knee-jerk rejection of the political and their work suffered for it.

It was in this context that Tsuchiya Yutaka showed up at the 1999 Yamagata International Documentary Film festival with The New God (Atarashii kamisama, 1999) and caused quite a sensation. Tsuchiya was himself a dedicated activist. He led Video Act! which was then the closest thing to a movement in the Japanese cinema world at the end of the 1990s. The structure of this organization bears out the era’s atomization of passion. It was (still is) a loose confederation of groups, connected more by a catalog and an internet site than anything else.

Before this, Tsuchiya’s most interesting work was the controversial What Do You Think About the War Responsibility of Emperor Hirohito? (Anata ha tenno no senso sekinin ni tsuite do omoimasu ka? [96.8.15 Yasukuni-hen], 1997). In this fine example of video activism, Tsuchiya and a friend go to Yasukuni Shrine on the anniversary of the war’s end to ask old people the question of the title. There are many impressive things about this project, both politically and formally. However, it is significant that these young filmmakers stepped into Yasukuni Shrine in the first place, let alone asking such a provocative question. This indicated a precious flexibility and an unwillingness to paint the right wing in broad strokes in order to dismiss it.

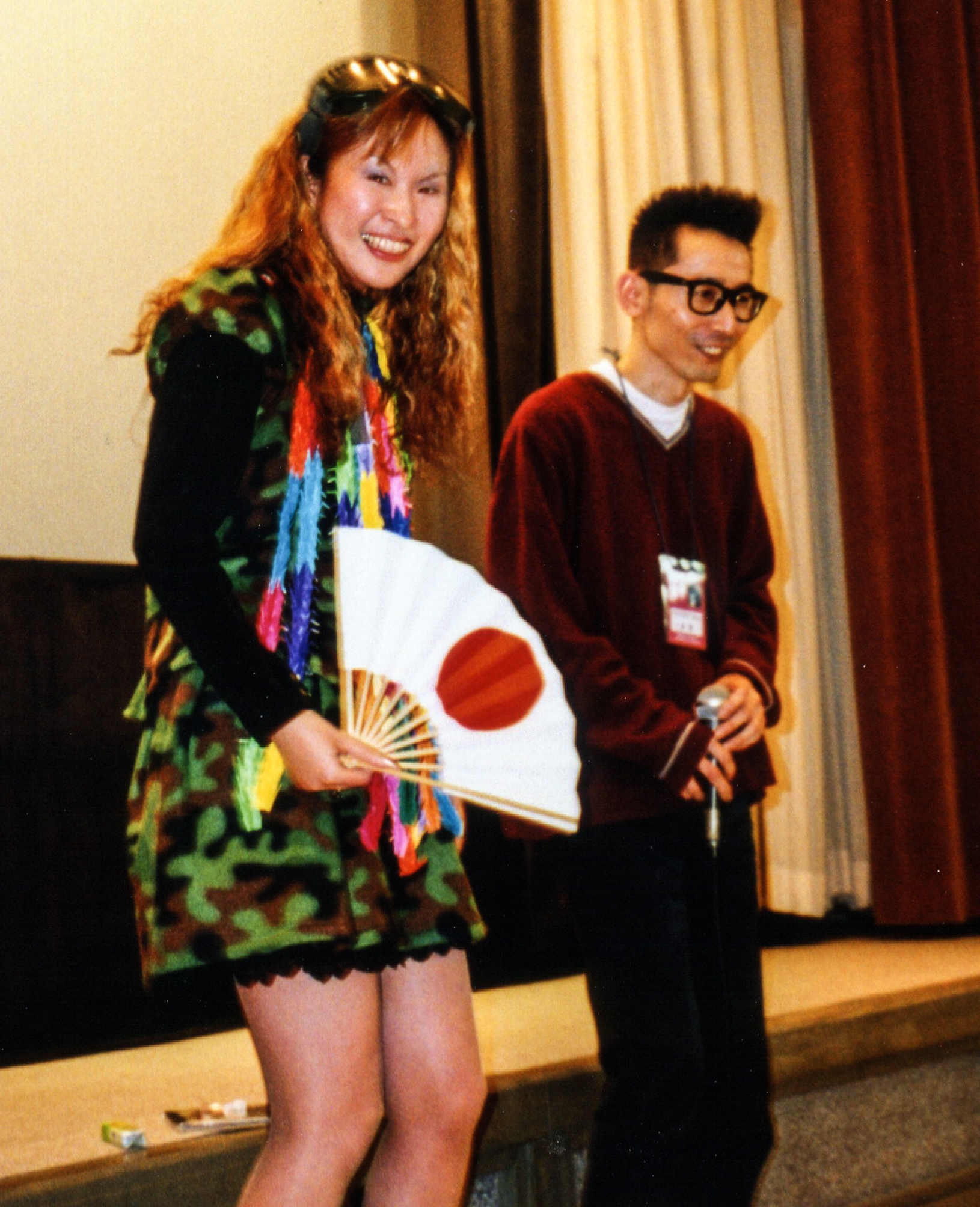

For The New God Tsuchiya capitalized on his flexibility and eagerness to engage people across the entire political spectrum. Its premise was simply startling: Tsuchiya the progressive video activist hooked up with an ultra-nationalist punk band, and each tried to figure the other out. He gave the lead singer, Amamiya Karin, a video camera and both she and Tsuchiya recorded the development of their unlikely encounter from their own perspectives. They treat the video camera as a kind of intimate, confessing their deepest thoughts. At one point Tsuchiya arranged for Amamiya to visit the Red Army members who hijacked a plane to North Korea back in 1970 and the visit forces her to think hard about her own life. As the deep similarities between the extreme left and extreme right become clear to her—including the intolerance of their politics and their untenable idealism—Tsuchiya and Amamiya find themselves drawing closer together, perhaps politically and certainly emotionally. By the end of The New God, they enter a romantic relationship, she quits her affiliation with an ultra-nationalist organization to rethink her musical activism.

The New God fits uncomfortably into the rubric of the private film. It constantly threatened to devolve into a love story, but Tsuchiya was too smart and too dedicated to an engaged documentary to let that happen. It started out looking like a somewhat conventional documentary until he handed a camera to Amamiya and her guitarist Ito Hidehito. From that point on, they became collaborators, something quite novel to the personal film as it was construed in Japan. In addition to the footage each shoots, all three offered their own voice-over commentary on the soundtrack. Tsuchiya made great use of the confessional mode that seems so specific to video as a medium. When they turned the camera on their own bodies, they constantly reflected on the latest twists and turns of their encounter. It became a mutual self-reflection, energized by the fact that each speculated on the motives and emotions of the other. Some audience members complained of a sense of performance during these private sessions with the camera, but that is only a matter of course. All documentary involves performance, but it also provokes what never would have happened without the presence of the machine.

To focus on these matters of style would be to limit The New God to the confines of the “private film.” What generated this phenomenon was precisely a refusal to enter the world, camera in hand. It was a dismissal of the political and the engaged, and a concomitant retreat to the safety of the self, the family and the friend (or even the aesthetic). Tsuchiya cites their constant consumption of the newest of the new as a deflection of the emptiness this causes, a way of engaging something safe, or creating a seemingly solid place to stand. He suggests the other safe haven is the personal. This situation helps explain why most young filmmakers seemed unwilling to take their cameras into that troubling world out there.

Tsuchiya’s use of the private film constituted a critique from within, because instead of using the genre to confirm one’s identity and worth through public screening of the private sphere, he used it to engage the public arena with a resolute and refreshing passion. Bringing in the Red Army was a brilliant move, and reminds us of that other Red Army revolutionary=artist, Adachi Masao, who seemed to pose the choice in the early 1970s as one between politics and art. But like the reality of Adachi’s position, which was never an abandonment of art, Tsuchiya was dedicated to avoiding these kinds of either-or choices and traps. His commitment to escape the closed circuit of consumption and dedicate oneself to something larger was also a refusal to become dead-ended in the vestiges of Old Left party politics or New Left revolutionary politics. In 1999, I was not the only one who left the theater feeling like I had finally seen a committed, passionate, engaged documentary by someone from the new generation. This said, I must also point out that while the film broke down easy oppositions of right and left, new and old, private and public, it left everyone on shaky ground. This is why, in retrospect, it’s hard to see The New God, in the end, as a turning point for the Japanese documentary.

photo (c) Markus Nornes

Markus Nornes is Professor of Asian Cinema at the University of Michigan, where he specializes in Japanese film, documentary and translation theory. He was a programmer at YIDFF in the 1990s and beyond, and has also made films. His current book, the open access Brushed in Light, is on the intimate relationship of calligraphy and East Asian cinema.

http://www-personal.umich.edu/~nornes

Dr. Markus’ Yamagata Musings

(1) A Movie Capital Dir: Iizuka Toshio / 1991 / YIDFF ’91 Special Invitation

(2) Living on the River Agano Dir: Sato Makoto / 1992 / YIDFF ’93 Award of Excellence

(3) A Dir: Mori Tatsuya / 1998 / YIDFF ’99 World Spetial Program, A2 Dir: Mori Tatsuya / 2001 / YIDFF 2001 Special Prize, Citizens’ Prize

(4) Pickles and Komian Club Dir: Sato Koichi / 2021 / YIDFF 2021 Yamagata and Film

(6-final) Storytellers Dirs: Sakai Ko, Hamaguchi Ryusuke / 2013 / YIDFF 2013 SkyPerfectTV IDEHA Prize

![ドキュ山ライブ! [DOCU-YAMA LIVE!]](http://www.yidff-live.info/wp-content/themes/yidff-live_2017/images/header_sp_logo1.png)