Living on the River Agano (Aga ni ikiru, 1992) is historically significant for the way it firmly stands at the transition point between the postwar social justice documentary and a proliferation of nonfiction forms, between the eras of 16mm and video, and between collective and individual production modes. It’s also a great film.

Director Sato Makoto first contemplated a career in filmmaking in high school in the late 1970s, when Tsuchimoto Noriaki (the Minamata Series) and Ogawa Shinsuke (the Sanrizuka Series) dominated the nonfiction scene. While the student movement had already quieted down, the films by Tsuchimoto and Ogawa made him interested in the continuing struggles at Sanrizuka and Minamata. He became a member of the collective that shot The Innocent Sea (with Kakesu Shuichi, Katori Naotaka, Shiraki Yoshihiro, Sugita Kazuo and Higuchi Shiro, Muko naru umi, 1983). This was a Minamata film, and he drew on the national networks of Ogawa Productions and Tsuchimoto’s Seirinsha for distribution.

Then in 1989, he and a crew of seven went to Niigata to make a documentary on the other area where Minamata Disease had afflicted the people, the Agano River. The collective approach to cinema epitomized by Ogawa Productions was still prestigious and powerfully attractive, so the filmmakers decided to living collectively in Niigata with the farmers and fishermen they were shooting. At the same time, people in the film world were increasingly aware of the pitfalls and challenges of collective production and they wanted to avoid some of the problems they perceived in the example of Ogawa Pro. On a YIDFF roundtable (featuring Ogawa’s Assistant Director Fukuda Katsuhiko among others) Sato recalls what they set out to do:

The system of actually living and working somewhere no longer existed, but we were taken by the idea that we had found an opening that no one else had. We were very clear that the messages in our films should be different. We didn’t want to convey the whole of Minamata, but rather to film its daily life. We thought that our films should be personal, that we should try somehow to break down social problems and focus on how lives can be lived and on the individual. Our way of filming was very 70s in that we worked in groups, but we absolutely did not want collaborative work to be a hard and fast rule as it had been at Ogawa Productions. There, it was a matter of hierarchy and poverty. We decided not to give the director all the power, and not to exhaust crewmembers without giving them any reward. We were determined to pay them at least something. We were trying to create some kind of community, but after three years, we found that we were just like a miniature Ogawa Productions. I don’t think that this kind of thing will really succeed (Sato, et al., 47).

The film that resulted from this collaboration, Living on the River Agano, was one of the high points of 1990s documentary. However, the production proved rocky, highlighting the problems of the collective approach. In retrospect, it appears like something of an experiment, to test whether the prestigious method represented by the example of Ogawa Pro was viable in an age when filmmakers were increasingly turning to private matters. Sato’s comment above was provoked by something Fukuda said: “Film units have gotten smaller, with all the main filmmakers, like Kawase Naomi, working either alone or as a couple. Documentary filmmakers no longer get a film crew together to shoot movies. So it is not only the film subjects, but also the way people make films, that has shifted from the group to the individual. I have the feeling that Sato’s Living on the River Agano will be the last collective film in this sense” (Sato, et al., 47). Indeed, Fukuda appears to have been prescient in his prediction that this film was closing an era. Sato himself left collective production for the conventional mode based on an assembled crew.

The Yamagata International Documentary Film Festival played an important role in the production of Living on the River Agano. When they attended YIDFF in 1989, the collective was so poor that it had no money to stay at hotels; instead, they pitched tents next to a river under a large bridge. At the 1991 festival, Sato and his team travelled from Niigata to Yamagata to show a rough cut in the Japanese Films Panorama Theater program and get feedback. The feedback was intense and took them aback. I once asked Sato for specifics. However, he just laughed as he stroked the top of his head and said only that it really put them in a tough spot.

I do recall the first official press screening of the film in Tokyo. By this point, it was a highly anticipated film, and the theater was crowded with filmmakers, programmers and critics. After the film, Hasumi Shigehiko held court with the filmmakers in the lobby, effusively praising the film. Aside from his cultural capital, being a professor (and future president) Tokyo University, Hasumi was one of the most powerful critics in Japan. He would go on to be one of the film’s champions. And Sato needed that support because the film also had many detractors. They mainly kept their criticisms off stage and out of print, but people were often dismissive and sometimes brutal.

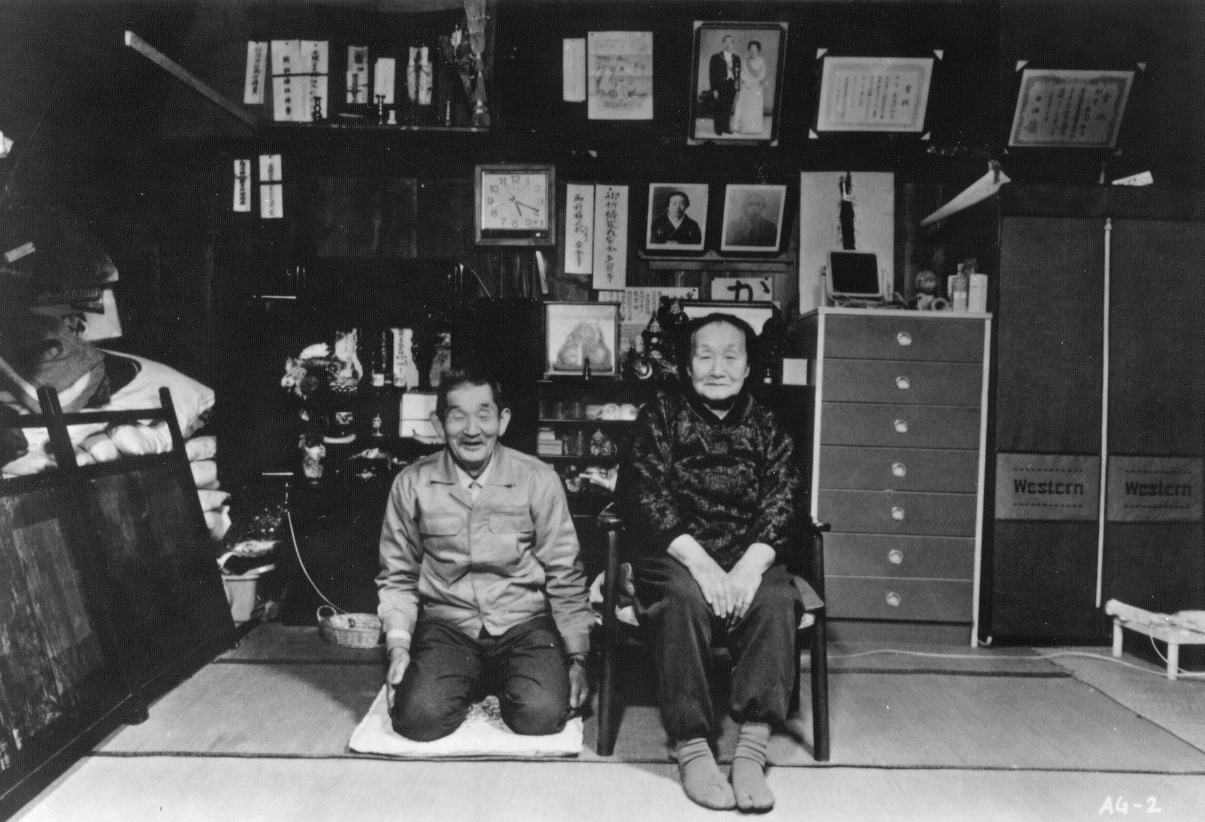

The main criticism had to do with the tone and stance of the film. This was not the in-your-face activist film that had dominated independent documentary since the end of the Occupation. Many had hoped for a concerted critique of the corporation that dumped mercury into the river, and one linked to government complicity and obstruction. In other words, they were using Tsuchimoto as a measuring stick and Living on the River Agano came up short. It’s true, Sato and his crew chose a more indirect approach that centered the film on the lives of the old people along the river. There are no clinical analyses of the disease and its horrible effects on the body. Rather, Sato mainly uses intertitles to explain the historical and political context of Niigata Minamata Disease. We see it registered on the human body mainly in indirectly, for example in the close-up of a gnarled, shaking hand.

Hasumi recognized and celebrated the continuities between the films of Ogawa and Tsuchimoto and Living on the River Agano. This is a film that was firmly rooted in the lives and being of the people before the camera. The filmmakers took a deferential approach to filmmaking that was cognizant of the power of the filmmaker, while trying hard to think and record from the place of the other. This is the source of the film’s powerful affect.

Over the years, Sato continually developed and articulated this approach as a filmmaker, writer and professor. In an era where independent documentary filmmakers were increasingly turning inward, to the self, through autobiographical modes, Sato asserted the importance of building the other’s gaze into the film. His most developed treatment is this theme may be found in the two-volume book entitled, Horizons of Documentary (2001). In his most powerful chapter, Sato pointed out that “The camera possesses a violent power. At the very least, for the person that is turned into a subject, being shot for a film, is like having something stolen” (104). Drawing on Oshima Nagisa, Sato asserted three principles for the documentary: “love for the subject,” “long-term recording” and “responsibility towards the subject” (169-171). Sato provocatively argued the camera bears “fangs” (kiba) that directors bare before their subjects, proposing that a politics and ethics for documentary filmmaking was inescapable. That anything else would be irresponsible. This was Sato’s starting point as a theorist, filmmaker and a human being. These are the very values and principles that animate Living on the River Agano.

With time, the whispered criticisms of the film have all but disappeared, and the rich achievement of the film has become crystal clear. Sato demonstrated a righteous ethics of documentary; indeed, he lived it. Unfortunately, that sentence was cast in the past-tense. Despite a cheerful and enthusiastic demeanor, Sato profoundly suffered from depression. Every once in a while, he would disappear from sight for the sake of self-care. However, in one particularly dark bout with depression, he tragically elected to end his life in 2007 at the age of 49.

However, his legacy, starting with Living on the River Agano, is as strong as ever. Today in Japan, any discussion of documentary theory and practice inevitably cites Sato. His pupils are working throughout the industry. His writings printed and reprinted. And at the Yamagata International Documentary Film Festival, one hears Sato’s name resound in the Q &As, panels and bars. At the 2017 YIDFF—a decade after his passing—Sato’s pupils mourned his death and celebrated his life with a series of discussions. The events climaxed with a big party…under the very bridge his crew slept under in 1989. There was a huge vat of potato soup, free-flowing sake, and Sato’s ghostly presence projected on the pillars of the bridge. Those present included his many students and collaborators, as well as the many filmmakers and programmers from across Asia who have been touched by Sato’s legacy. This, I think, perfectly sums up the spirit of Yamagata and the role it has played in the history of Asian documentary.

++++++

photos from 2017 (c) Markus Nornes

Sato Makoto. Horizons of Documentary (Dokyumentarii eiga no chihei, Tokyo: Gaifusha, 2001).

Sato Makoto, Yamane Sadao, Fukuda Katsuhiko, and Araki Keiko. “From Political to Private: Recent Trends in Japanese Documentary,” in The Pursuit of Japanese Documentary: The 1980s and Beyond (Tokyo: YIDFF, 1997).

Markus Nornes is Professor of Asian Cinema at the University of Michigan, where he specializes in Japanese film, documentary and translation theory. He was a programmer at YIDFF in the 1990s and beyond, and has also made films. His current book, the open access Brushed in Light, is on the intimate relationship of calligraphy and East Asian cinema.

http://www-personal.umich.edu/~nornes

Dr. Markus’ Yamagata Musings

(1) A Movie Capital Dir: Iizuka Toshio / 1991 / YIDFF ’91 Special Invitation

(3) A Dir: Mori Tatsuya / 1998 / YIDFF ’99 World Spetial Program, A2 Dir: Mori Tatsuya / 2001 / YIDFF 2001 Special Prize, Citizens’ Prize

(4) Pickles and Komian Club Dir: Sato Koichi / 2021 / YIDFF 2021 Yamagata and Film

(5) The New God Dir: Tsuchiya Yutaka / 1999 / YIDFF ’99 New Asian Currents

(6-final) Storytellers Dirs: Sakai Ko, Hamaguchi Ryusuke / 2013 / YIDFF 2013 SkyPerfectTV IDEHA Prize

![ドキュ山ライブ! [DOCU-YAMA LIVE!]](http://www.yidff-live.info/wp-content/themes/yidff-live_2017/images/header_sp_logo1.png)