Yearly Archives: 2021

Jason Tan Liwag

We begin submerged in water. We awaken to the image of silt and then, from the depths of the ocean, we emerge, almost as if rising from baptism, and are introduced to an island. There are little signs of life—a snail crawling on a rock, the sound of birds, and a forest in the distance. Turbulent waters thrash violently in the peripheries of the frame. Against the rock, we see a shadow, extending and flexing. We gaze at images of what appears to be an abandoned resort, the sum of its parts inviting a question: Where are we?

This is how The Still Side begins.

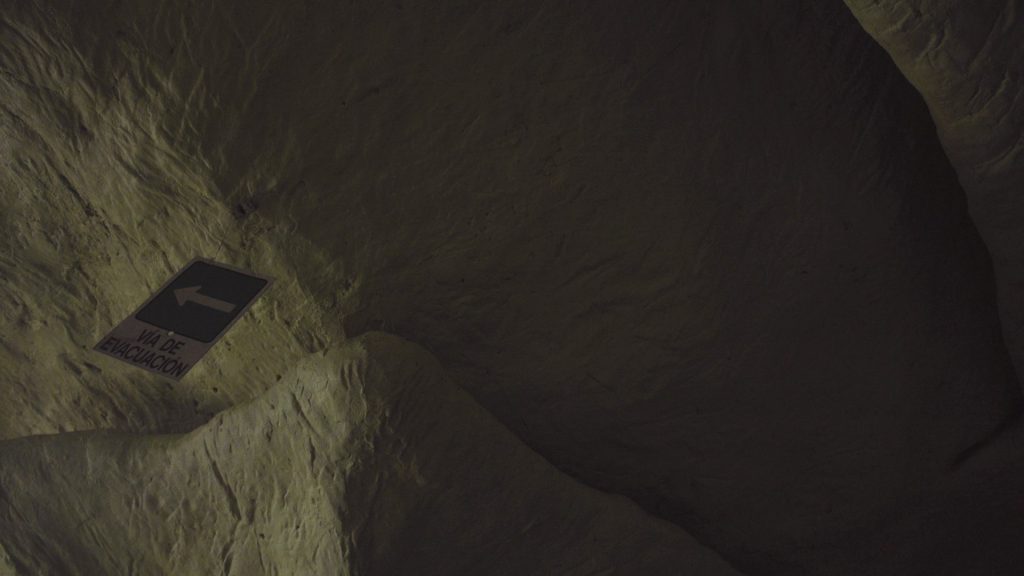

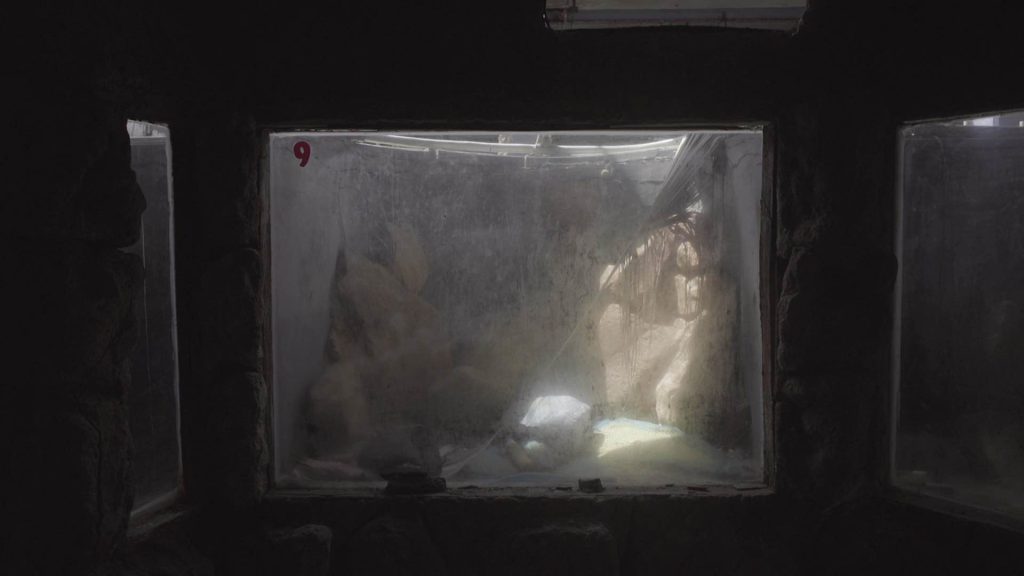

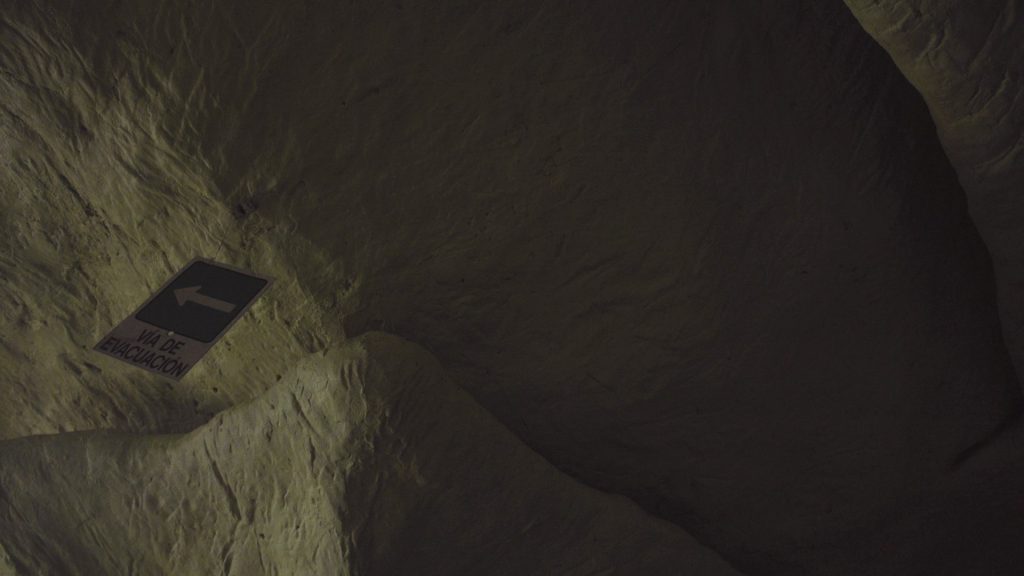

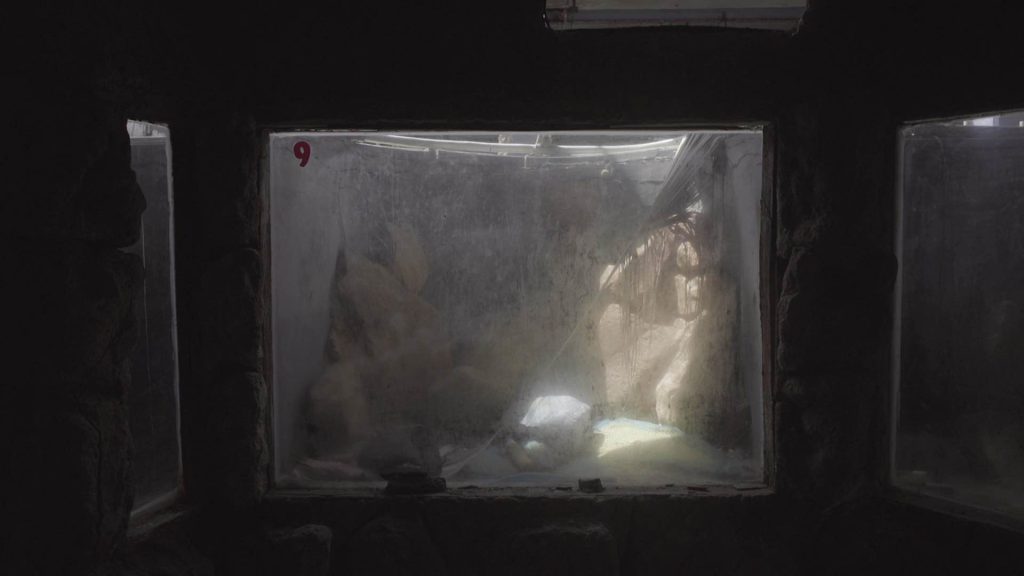

The desolate landscape of the Capaluco—once a resort, a temporary haven, a place of leisure and pleasure—is now left empty. The reasons for its abandonment are visible through the architectural aftermath: cracked walls, broken chairs, dust everywhere, plants and water where there shouldn’t be. Morning announcements cut through the silence to announce the history of these spaces, a glimpse into its lively past and empty future. In each scene, life carves its way through the architecture: moss and vines grow on buildings, tubes funnel symphonies instead of water, curtains dance to the wind, and algae and fish create homes out of underwater pillars.

We experience these through the perspective of the Siyokoy, whose face is unknown but whose presence is asserted through its shadow. Often spoken of as a vile, man-eating sea creature, it is carried onto this island by a current that connects Manila and Mexico—an umbilical cord between countries with a shared history. Echoes of life are painted through the soundscape and one wonders if the Siyokoy understands the purpose these spaces once had. We explore parts of the island along with it as it leaves the ocean for land, abandoning its history and myth of violence. In a place that holds no competition or interference, its discomfort is transformed into peace; it becomes a pioneer species.

In the process of watching The Still Side, I cannot help but think of ecological succession: how biological communities change over time after a major disturbance. From the trees that fall in the middle of the forest to asteroids that wiped out the dinosaurs, these disturbances shake up the status quo within a community to be of service to life in the long run; a form of self-destruction for the common good; an annihilation that allows life to adapt and prevail.

The human condition is threatened by similar disturbances: collapse of the neoliberal economy, labor strikes, changes in the media, a global pandemic. Though these threats remind us that life is fickle, it is possible to live even in the presence of destruction and destitution. Revereza and Fusilier contemplate the sustainability of these architectural marvels in the face of time, nature, and evolution, but also express hope in the persistence of these structures, even if their revival in the hands of the human race remains unsure.

In a way, the documentary captures this struggle to preserve life in a way that keeps its being, unlike in the colorful murals of animals, timeless but lifeless suspensions. By blurring the line between the artificial and the natural, The Still Side reveals how myth and reality can co-exist within the same space to tell larger and more complex truths about the politics and purpose of creation, preservation, and destruction of art and architecture. In the same way that each frame must be replaced by another for the film to move forward, we find our lives in the midst of an ecological succession—in order to keep on living, we must allow the current to carry us wherever we need to go; in medias res only until the next disturbance; an acknowledgement that life does not only occur in one place and that home can be many places.

Revereza’s experiences as an undocumented immigrant in the U.S. influence not only the subject matter of his films but the way his films are created. In his previous work such as Distancing (2019), No Data Plan (2019), and Disintegration 93-96 (2017), images are fleeting and ambient sound is overlaid with artificial ones. Motion is imperative and attachment often serves as baggage due the persistent threat of displacement, even if the assailant is absent from the frame. In each of his films, migration always means separation: from family, from the state, from earthly belongings, from his concepts of himself. Free from these tethers, Revereza was free to improvise and discover but also turned himself into a perpetual outsider; an anonymous and liminal figure whose life is reflected in his films only in fragments.

But in The Still Side, the usual shakiness in his camera, the body that is associated with this movement, is no longer running away from anything. In a way, Fusilier’s presence as a co-director allows Revereza to anchor himself in this fictional Mexico and this is reflected in the camera movements: how it lingers or slowly pans across the vast space. In this land where there is neither enemy nor friend, there is room to breathe and a chance to take time. Revereza and Fusilier are pioneers here and repurpose a space historically failed by the neoliberal, capitalist, and colonial society into a home where those unjustly treated by these systems can return to; a place where men can no longer treat each other like monsters.

Van Do

Watching different films by the same filmmaker (especially if it’s done chronologically) feels like a prolonged conversation, each time a revelation. The Still Side is not the first film by Miko Revereza I’ve watched (except that this film is co-directed with his partner Carolina Fusilier). Earlier, I saw another short film by Miko Revereza called Distancing in this year’s Seashorts, in a program curated by Chris Fujiwara. With each work, you get to know better a person—his ways of seeing, his state of being, his influences. I am first drawn to Miko Revereza’s work(s) because of their writerly, visually and textually poetic, stream-of-consciousness quality, especially shining through in the pacing of his spoken words and his free association of references. Another element I’ve picked up in his approach to his filmmaking is his ability to turn real-life situations into art, in a way, embracing life with all its flaws and unpredictability, or in Miko’s words, “playing things by ear.”

The Still Side was born in Mexico out of a strange circumstance of our time: travel bans started to take effect in the Philippines, where Miko Revereza was based then, at the moment he flew to Vancouver for an artist residency, just to find out upon arrival that the residency had been turned online. Stuck in limbo as he couldn’t return to the Philippines nor could he stay in Vancouver, he decided to fly to Mexico, where Carolina Fusilier is based. What at first seems like an unfavorable situation was turned into an opportunity for collaboration of two artistic visions, between a visual artist and an experimental filmmaker. Indeed, what ends up as we see in The Still Side is a nice fusion of the best of both worlds: it’s as if Carolina Fusilier’s eye for the aesthetics of structure, space, and composition is merged with Miko Revereza’s poetics of narrative-making, sound design and quirky syntax of intertextual referencing. And of course their artistic luggages are in no way exclusive of one another, as I can imagine how their interests, inclusive of both similarities and differences, must have informed and complemented the process of exploration in the making of the film. In a similar vein of birthing art from life, Distancing was made as response to Revereza’s decision to leave America for the Philippines, which would potentially ban him from coming back for 10 years as he was to embark on this one-way, self-exiled journey. The film thus bids a fond, nostalgic farewell to a place that both raised him and denied his existence.

In his films we see lots of movements: physical, mythological, technical, political, poetical. His itineraries—across the United States, from the United States to the Philippines, from the Philippines to Mexico—somehow informed and gave form to his films. Through the medium of the moving image, he time and again returns to explore with great poignancy the differing connotations of displacement and exile. In his recent interview on the Criterion channel, he said, “It was important for me to realize that the style of the camera movement is so connected to my body—my policed body—moving through the United States.” This statement was made in direct reference to his feature film, No Data Plan. But it seems to me that the style of camera movement is of equal significance for investigating the aesthetic and conceptual endeavors of Distancing and The Still Side.

Distancing was shot mostly handheld, from which the breaths, points of view, and attention of the camera operator (Miko himself) might be told. With this film, we are given so much intimacy with the people and reality in front of the camera. Shaky and at times out-of-focus, these handheld movements render the camera into a body with its own physical conditions and mental state. This body is indeed breathing hard and is emotionally shaken by watching the life of his grandfather on the verge of passing by. This choice of camera style seems fit also because the filmmaker is making a closer study of this perplexing identity suddenly made anew. If the cameras behind The Still Side are also a person, they must be much calmer, more measured, but no less thoughtful in grasping a much larger, more foreign landscape. With static frames and slow pans sometimes, the cameras move effortlessly across different heights, sizes and depths of the island of Capaluco — inside the architectural aesthetics of an abandoned resort in Mexico, beneath the waves of the sea, beyond the transparent sky, into the polyphonous jungle, around the remnants of so-called civilizations. The regular shift of shot sizes, as well as the well-designed soundscape of the film, allows us viewers to be fully immersed in a setting characterized by the prosperity of non-human beings, such as flora and fauna, insects, sea creatures, and perhaps ghosts that inhabit the island. All at once, it’s like we are transferred into the bodies of outer space explorers landing upon Earth in 10,000 light-years’ time and those of microorganisms tiptoeing across the dead bodies of sea and forest creatures.

In The Still Side, the filmmakers see no boundary in moving between fiction and documentary, between myth and reality. Siyokoy, a Filipino migrant sea creature crossing the ocean from the Philippines to arrive at Mexico, is layered in the narrative of the film, but we never actually see it on screen. Capaluco, the name of the fictional island in The Still Side, is based on the Mexican coastal resort city Acapulco. This is how the filmmakers like to play with their imagination, as it breathes mystery and life into a space (in actuality) full of absence and emptiness.

Martin Lukanov

From its very beginning, Miko Revereza and Carolina Fusilier’s The Still Side announces itself as a film obsessed with the minutest details of neoliberalism’s consequences. Consisting predominantly of perfectly framed closeup shots of the deserted parks and crumbling buildings of the abandoned semi-imaginary all-inclusive resort island Capaluco (Acapulco with each consonant moved one space to the left), the film gives us almost no context about what happens onscreen. Not that we need any.

Each of us, irrespective of where we are from, has seen such a place, if unlucky enough, has probably even been to one. Because such places are the result of nothing else but neoliberalism and its best friend, consumerism. Statues and columns next to “exotic”-looking monuments and ornaments and cafes in cheap movie set-like caves. Each of them simulacrum of an original uprooted and displaced by colonialism, reproduced ad infinitum only to become a background of a gaudy all-inclusive dream resort. What we see might be the imaginary Capaluco, but it might as well be in any place on Earth punished with an all-inclusive resort. Or is it Skopje beamed back to us from the future? It’s all of them and none, everywhere and nowhere, seem to say Revereza and Fusilier. Globalization writ large.

The spaces we see are crumbling and devoid of people, but not completely dead. No, that would be too humane for them because then they could be rebuilt and used for something else. Instead, they are all left in a state of limbo. Ghost spaces tethered to this world with the chain of bureaucracy. We are reminded of that time and again. A drainpipe that sucks all the water just to spit it back again. Dismantled sewage pipes that emit ghostly drones, as if trying to tell us something. Each gurgle of water and wail of the wind a bit quieter than the rest. Always dying, never fully dead.

Though dilapidated and bereft of human presence, the artificial caves, gaudy statues, and papier-mache monuments that fill this imaginary-yet-real island are teeming with microscopic life. We don’t see it for the most part, but we hear it. A lot of it. High pitched screeches on top of effervescent drones and micro crackles composed so well that they bring to mind the music of Toshimaru Nakamura and Richard Chartier. It is as if microscopic squatters are occupying these abandoned places, slowly changing them, making them fully theirs.

The beauty of the artificiality of the spaces and highly abstract (and utterly enjoyable for all fans of electroacoustic improvisations and microsound) sound design is offset by the pseudo-philosophical (and at times preachy) dialogue between the filmmakers. Delivered with the type of casual tone that is supposed to convey that what is told is profound, it is anything but that. Rather, the content of the filmmakers’ dialogue reminds me of the freshmen I teach in university—feeling like they know everything, though knowing almost nothing, they utter obvious statements using big-sounding terms.

This is best exemplified by a story about a Siyokoy, a mythological merman from the Philippines, told by Revereza early on in the film. Its length implies that it is important for the film. How, though, we are only left to wonder. There seem to be no direct links to it in what is shown on screen. Neither is it mentioned at any other time during the voiceover. Even its connection with the themes of the documentary is tenuous at best. Is it chosen because it represents the ways neoliberalism and consumerism destroy nature and displace life? Or the ways they regurgitate culturally important symbols to the point of them becoming nothing? Or maybe even we, the viewers, are this mythical merman, as the opening shot suggests. Well, we don’t know. And the sad fact is that it doesn’t seem like the filmmakers do either.

Though visually and aurally engaging, The Still Life is rendered almost impossible to take seriously by a narration that seems to say nothing valuable about the topics the movie seems to engage with. We can just hope that one day its soundtrack will get a separate release. Hopefully by a good label. Preferably on a vinyl.

Linh Than

Describing itself as “somewhat of a science fiction embedded within a documentary,” The Still Side (El Lado Quieto) indeed lives up to its humble disclaimer: it’s somewhat fictional, somewhat not, somewhat contemplative, somewhat pressing, somewhat… Here, one could fill in the blank with anything, for the directors, Miko Revereza and Carolina Fusilier, seem to lose touch of the film’s sensations altogether; instead, they get swallowed by a vain desperation to aestheticize anything in view, only to be left floating face-down amid a flotsam of filmic elements bereft of meaningful connections.

An undocumented immigrant in America for 26 years, Miko Revereza embraces themes of distance, separation, and longing in his films. This time, the director really finds himself cast adrift in Mexico due to the pandemic. In a sense, the mythical creature—the viewpoint of the film, Siyokoy, is Revereza himself, who also got washed ashore far from their homeland, the Philippines—or did they choose to come here? Dense yet directional, the vigorous current seems to build up expectations of something exciting once the camera cuts through vigorous bubbles into the light. However, as promising as the idea is, reality borders banality.

One can always find refuge in the better parts of a film and justify our affection with generous sensibility. The Still Side is indeed interesting: the film ruminates on the idea of making a habitable home within destruction. However, the film lacks for me this organic sense of exploration—the meditative period only succeeds a whirlwinding storm of discomfort. This immediate and perpetual insistence on neat, beautiful cinematography not only undermines the viewers’ ability to immerse with all senses into the space, but also distracts from engaging in deeper contemplations, for curious eyes don’t wonder at perfection.

It’s almost so pretty that there’s no sense of life. Intercutting among Greek mythologies and themes of abandoned glory, lostness, and mystery, the film is momentarily saved by the slow promenades against a backdrop of the theme park’s audio guide and announcements, but is then again lost to a consecution of waterpark ruins framed in perfect symmetry, perfect to the point of affectation. These static shots create a visual conflict with the wandering POV shots of the abandoned remnants, a conflict that breaks the flow of contemplations apart. The editing is meditative, but maybe too “full.” Each image, whether belonging to a consistent themed series: paint-chipped animal murals or washed out waterslides, emptied cages or opaque aquariums, whether humming industrial ASMR or calling out the single dead leaf, precedes the next in what I deem as nonchalance. Can’t they be slightly hollow, since this is somewhat a science-fiction film? Yes and no. I have an abundance of patience for slow cinema, only when it’s loud and solid, in intention. All these extended shots of semi-working debris and natural residents (snails, fox, fish, ants,…) fail to capture the lifeblood still throbbing in such desolation simply because they are not honest—what we see is more the viewpoint of a controlled robot than of a Siyokoy, even less of a sensorial man. And I’m sure the main character is anything but a robot.

The spatial study along this quest for philosophical meditations is further muddled and diluted by the discussions between the two offscreen artists. Although sounding intimate in their whispery tones, the content of their talks is sterile, superimposed on visuals that are also sterile. Looking at the beautiful sun that resonates weakly with the rest of the film while listening to a high-school-lunchtime-type discussion about power and empire, I realize I’ve already understood all there is to understand. There seems to be a story about the resurrecting power of death calling for some remorseful resolution in response to post-industrialist decay interwoven in images of life (or the lack of), naturalistic recordings of ambience (lifeless or alive), but it is lost, or forgotten, in the gaps here and there between the filmmakers’ attempt to micromanage and their compounding a joke about a novel shape-shifting technology for future inhabitants, like those customizable emojis on social media, that is hardly funny. How can this bring about the lightness of meditation after such an arid and controlled presentation? After reaching the end of the preach, what more (of this future, or of this film) is there for the audience to conceive?

There are plenty of interesting elements and decisions attempted in the film, but merely nothing holds them together. Separately, they shine in glamour, but each glamour cancels another out. Intentional but loose, beautiful but barren, this is somewhat of a documentary that adopts a faux identity of a science-fiction in hope of redeeming its dreariness.

John Patrick Manio

There is this one poem that remains my favorite—Percy Shelley’s “Ozymandias.” Its persona met a traveller who saw a massive but withered ancient statue on the road. It has a sign that says the statue is Ozymandias, king of kings. And he wants to brag about his dominion. The poem ends with passages describing what this dominion has become over time: nothing. The great Ozymandias and his works became nothing.

I often dream of Star City, a famous amusement park here in the Philippines. But my dreams would often depict it abandoned and in ruins, with its rip-off Disneyland attractions and kitschy architecture and design haunting the place. But the dreams are not nightmares, I was never terrified of them. In fact, I was always amused by its eeriness—more amused than the amusement park itself. Star City burned down to ashes two years ago. Now, my dreams are more impactful, because that abject fantasy world remains existent only in them.

The Still Side is like my dreams, as films are like dreams. Miko Revereza and Carolina Fusilier capture Capaluco, a fictional resort vacation island in Mexico through fragmented shots put together to create a narrative. Old megaphone announcements haunt the place, serving as guide to the architecture and attractions within the resort. What Capaluco actually looked like in the past is forever blurred like how memories are never solidified.

The Still Side is like the poem. But instead of words, it utilizes images and sound to picture desolation. Although, the common theme between the two is the fickleness of human hubris. Pool slides that reach up to the skies are left dry and rusting. Cages that house animals are now empty. Buildings are eaten by waves crashing to its foundation. What arrogance it is that what remains most intact is a copy of a pantheon by the gods.

The “eerie” is defined by cultural theorist and philosopher Mark Fisher as absence where presence should be. Capaluco should be overrun by many people. But alas, not only did people disappear but so does capital. The “eerie” is also presence in a space where there should be absence. Like the foreigner-monster Siyokoywho shouldn’t have been there, detachedly wandering along the ruins of Capaluco, I find myself in my dreams in Star City alone and surrounded by bootlegged visages of foreign capital that shouldn’t have been there.

A zoo where there remains no animals. A pleasure resort where there remains no pleasure. A business where there remains no business. Capaluco isn’t real, but it remains real in our imagination. The derelict locations captured are real, somewhere in the world. What purpose does a Filipino like Revereza have in shooting Capaluco? Maybe he and his filmmaking partner are looking for traces of the colonizers. Maybe, like the Siyokoy, they themselves want to invade this barren space like what colonizers did to their home country once. Perhaps, like the filmmakers, the Siyokoyis an immigrant displaced in a foreign land.

The abandoned island of Capaluco looms like a spectre haunting us—being a reminder of a once booming economy. The Still Side unearths this ghost town. Revereza and Fusilier are like the traveller in “Ozymandias”pointing to the withered statue and the vastness of nothing, as if they are our tour guides.

I met a traveller from an antique land

Who said: “Two vast and trunkless legs of stone

Stand in the desert. Near them, on the sand,

Half sunk, a shattered visage lies, whose frown,

And wrinkled lip, and sneer of cold command,

Tell that its sculptor well those passions read

Which yet survive, stamped on these lifeless things,

The hand that mocked them and the heart that fed:

And on the pedestal these words appear:

My name is Ozymandias, king of kings;

Look on my works, ye Mighty, and despair!

Nothing beside remains. Round the decay

Of that colossal wreck, boundless and bare

The lone and level sands stretch far away.

— Percy Shelley’s “Ozymandias”

Christopher M. Cabrera

Slow and contemplative cinema is difficult to achieve and even more difficult to master. With The Still Side, directors Carolina Fusilier and Miko Reveresa utilize this meditative and observational mode to explore the remnants of an abandoned resort in Mexico. But what the camera finds among the empty disco halls, barren hotel rooms, and corroding concrete is more than just a passive record of a curious local spot left to time. The film explores the potential for the observational gaze to rediscover space—and, to a large extent, sound—a statement of cinema’s power to embed meaning in what seems like otherwise trivial observations of still life.

The film begins as the camera is swept along by ocean swells before it lands on the Capaluco resort’s rocky shoreline. The camera begins by looking at stationary shots of crevices in the rocks, pools of water, setting a rhythm for the rest of the film’s visual language. The sound of waves lapping up against the rock formations and the deep echoes inside oceanside caverns punctuate the soundscape. Almost barely noticeable on screen is the brief appearance of a curious shadow of a tentacle-like appendage swaying slowly against some rocks.

As the camera moves deeper into the resort the film intersperses a conversation between the directors, who suggest a creature, the siyokoy, who has been swept up in the ocean currents from the Philippines, now wanders in awe of these structures left by humans. Is this the mysterious shadow on the beach? Is what we see in the film from the point of view of the creature?

This extra layer of “fiction” seeps into the rest of the film as the camera continues to slowly and quietly observes the resort’s interior. Fiction and reality begin to blur and what we see can no longer be taken at face value. Shots of the architecture take on an otherworldly appeal, the ambient soundscape becomes more unsettling, the empty buildings seem post-apocalyptic.

But the film does not wander too far off in this territory and the directors even pose this narrative in hypothetical terms. The Still Side still remains close to reality, a reality where the abandoned resort certainly does exist. The deeper we are taken into the uninhabited structures the more it becomes clear that the framing of this abandoned town is not for mere visual pleasure but to reflect on the real-world impact and implications of these decaying sites. When the camera is fixed on the wreckage of boats, the empty animal cages, and the corroding materials that have become ornaments of marine life around the resort, we are invited—through the slow-moving camera work—to think deeply about the effects of rapid development and the imprint of consumer culture on the environment. By thinking through landscape—one thinks of the discourse on landscape in Japanese avant-garde cinema—The Still Side presents a subtle yet effective mode of questioning societal ills, one that obscures spectacle in favor of contemplative long takes on seemingly insignificant views of the resort.

But the camera does not frame the area as all rot and decay. One of the most important rediscoveries of the film is how the abandoned resort is still full of beauty and life. The once gaudy disco, the scribbled graffiti, the chipped paint on the doodles on the wall, the mold growing on statues—there is something aesthetically pleasing in capturing these objects left behind, in reframing them with the camera in this new context as they stand as testaments to the past. While the exotic animals in the zoo and aquarium have been replaced by an overgrowth of nature, the filmmakers find the spaces repurposed and effectively reframed by new fauna: stray cats, ants marching, and bursting with life in the sea. The ambient sounds that haunt the resort, which achieve a sizable resonance when paired with the film’s still images, are in themselves a work of art, otherwise unnoticed traces of the past and the present that the filmmakers have unearthed from the ruins.

While the slow and contemplative mode of cinema may not be for everyone, The Still Side reimagines and rediscovers the contours of a forgotten site while providing viewers an intimate and unhurried engagement with cinematic space.

Jason Tan Liwag

Dorm begins by revealing its monster.

At first glance, it’s just another bunk bed in the dormitory. But with a switch and a prayer, it transforms: hands and feet stretch out from within the bedframe, its skin an amalgamation of metal, plastic, and cloth, its body made of hidden possessions. Its presence is a declaration: we are in another dimension.

Bordering on fiction, Dorm explores the life of female Vietnamese workers in a communal dormitory. There are rules here: everything is public, your bed is the only thing you own, and silence is a form of respect for others. Within the dimly lit space and walls made of beds, the film traces the lives of the women as they help a newcomer assimilate into the space, contemplate staging a workers’ strike, and prepare a theater piece: improvising dialogue, practicing lines, creating set pieces, and directing one another. The perpetual darkness and the close proximity of the individuals in the scenes prevent the audience from noticing any temporal progression.

The camera remains static and steady throughout most of these scenes, with some closeups and quick cuts to show the art and the faces behind them. Every now and then, there are sudden movements that tether us to reality—a pan that happens too early or a quick change in angle—inadvertently announcing the existence of an unseen observer. As the film progresses and culminates in a violent upheaval, it sheds its fictional elements in exchange for cinema verite: using framing and architecture to obscure the aggression, careful not to dehumanize its subjects further.

In the final ten minutes of the film, it opens up: the light pours in from the ceiling, opening up to a wide shot of an entire warehouse that reveals the dormitory to be a stage, its occupants workers who are reenacting their own experiences for the camera, performing their pain for others to witness. As the activists march out, and the other workers are left behind, we are left to make sense of the aftermath of the image.

There are many ethical limits to documentary films: How do you remain truthful without being exploitative? How do you create a narrative without crossing too many boundaries or disrespecting privacy? What are the responsibilities of the filmmaker in the face of suffering? In such circumstances, when the strikes are illegal in Vietnam and the working conditions brutalize individuals, there are too many risks that compromise the subjects if the form adheres strictly to the cinema verite demanded by “traditional” documentary.

Documentary fiction allows space for these limits to be addressed because documentary is not reality itself, but a reflection, refraction, and reconstruction of an accumulation of experiences. Role-playing has been used countless times to prepare women for the harsh world to come and to protect them from the shock and the unexpected aftermath of violence. Like in director So Yo-hen’s previous film Gubuk (Hut), theater becomes a way to reclaim narratives of oppression, performance a way to process trauma, and film a way of enabling and capturing this progress.

By blurring the lines between documentary and fiction, Dorm is in service of larger truths. In the words of one of the women: “These pictures were drawn by others, but the issue is everyone’s.” Regardless of whether what we are witnessing is purely fictional or not, these larger systems of exploitation are very much rooted in reality, and their effects are still felt by those around them. The hybrid format allows a form of cinematic atonement, a chance for these women to rewrite their lives and the way they are treated by these systems that seem immovable and unchangeable, at least on film.

In acclaimed writer Leslie Jamison’s essay collection The Empathy Exams, she examines how different experiences shape our definitions and practices of empathy. In her essay “The Lost Boys,” Jamison examines the role of documentaries in the development of empathy. She writes: “If it’s all edited anyway, if it’s all artifact, couldn’t it take another turn? Couldn’t there be another ending?”

Turns out, there can be. Dorm is proof of that.

John Patrick Manio

To put it succinctly, Nude at Heart is a eulogy to a dying Japanese art. Okutani Yoichiro documents the behind-the-curtain lives of multiple odoriko (Japanese for dancing girl) traveling around the last 20 remaining Japanese strip theaters. Odoriko are theater performers that center their performances around stripping. The audience aren’t allowed to touch them, nor are the odoriko allowed to have sexual relationships with them. The audience are mostly older men. The young don’t really go to these strip theaters anymore because they have been rendered almost obsolete amidst newer forms of entertainment.

It’s easy for someone coming in at the documentary to assume that Nude at Heart would feature victims of the sex industry. But it’s a surprise to realize that it highlights dignified women lamenting over the future of their respected theatrical stripping. Older odoriko complain about the changing tradition from sensuality to physicality. Younger odoriko ponder their eventual career options whenever all strip theaters close down. “It’s not prostitution,” says one of the dancers.

Emphasis should be given to “Japanese art,” because the subject matter is culturally sensitive. Of course, there are still layers of class and gender that can be extracted from the text. However, the documentary doesn’t really present them at the forefront. Maybe a Japanese sensibility is needed to fully grasp the nuance of its subject. As an outsider, how should one evaluate the politics of the subject properly in regards to the grander scheme of things in Japanese society? At least one can describe how they feel in regards to what the documentary presents.

We see several performances, but there is no nudity shot on-stage where it is

spectacularized for the audience (both those in the theatre and us watching). All the nudity is from backstage, where odoriko prepare for their respective shows. Nude bodies are seen walking around, applying makeup in front of mirrors, and getting on their costumes. Nudity in Nude at Heart is presented as natural, not sexual. These nude bodies are people with names and personalities, about whose professional lives the documentary has already provided backgrounds.

Can the film be accused of a male gaze? Nude at Heart is actually a re-edit by editor Mary Stephen of Okutani’s original film, titled Odoriko. According to reports, some similar footage is used, some new scenes and audio are introduced, and a different structure is presented making for a more candid and intimate introspection by Stephen. Okutani’s shots, while innocent by themselves, can easily be mistaken for being exploitative if placed or built up differently in a careless way. Stephen’s pacing and sequencing guides you maturely, laying out elements so as to avoid maliciousness.

Shot with a mini-DV camera, the documentary has a home video feel. The gaze, while still voyeuristic as it lurks at room corners and behind door frames, feels at home. It is leveled equally with the people. Minus in one scene, it’s presence isn’t acknowledged. The picture quality is very fitting for the material: an outdated technology for an art form being phased out. It looks beautiful not because it is crisp, but because it is degraded, giving it more sentimental value.

Nude at Heart ends after the last performance by Rena Itsuki, a veteran in her profession. She shows us her preparation process. She tidies up the makeup room. She wipes the mirror that has taken care of her all this time. “Odoriko don’t do this anymore,” she says, referring to the ritual of wiping the mirror. It probably won’t be used and wiped again. The theater where she has been performing for years shuts its lights permanently, and the darkness of the stage is the final image we see as the credits start to roll.

Van Do

I have always had a soft spot for Grandmas. I guess it is because of my own Grandma. I didn’t anticipate meeting her in Songs Still Sung: Voices from the Tsunami Shores. But I did. Let me tell you why.

Songs Still Sung begins with a poem recited by one of the Grandmas of the film. We then learn that this poem was translated from standard Japanese into Kensengo, the Kensen region’s dialect of Japanese. This translation emerged from a series of translation workshops called Poems of Ishikawa Takuboku in the Voices of Tohoku Grandmas, which were led by poet Arai Takako in Ofunato, Iwate Prefecture. The Ofunato shores have witnessed and endured three tsunamis over the course of a century, in 1933, 1960, and 2011, and the Grandmas in the workshop have lived through at least one or the total of the three of them. In this workshop, the Grandmas were invited to choose to their likings the poems of Ishikawa Takuhoku (a 20th-century Japanese poet also born in Iwate, that was renowned for his poems written in standard Japanese) and translate them into Kensengo, the dialect that they were born and grew up with.

Why do I find this a stunning approach to a film about survivors of tsunami? All too often, documentary films made about people surviving a catastrophe or trauma paint a horrendous portrait of the physical and psychological scars left upon such survivors; they can easily fall into the stereotypes of either dramatizing the pain and suffering, or overglorifying the resilience of those who remain. Grandmas. Poetry. Translation. To me, the combination works just right, in a form of poetry readings, observation, and interviews that is simple, straightforward, and unadorned. Perhaps because of that, Songs Still Sung is rendered into a powerful ode against forgetting.

After a few minutes into the film, it slowly dawns on me what the translation workshop is actually about. In Japan as much as everywhere else in the world, globalization and fast-paced modernization have brought about the inevitable assimilation of cultures, in which a variety of cultures or languages that are deemed “minor” are easily subjected to reduction and swallowed up by the “major” ones in a brutal process called standardization. The Kensen dialect is currently on the verge of disappearing. The grandchildren of these Grandmas go to schools where they are taught standard Japanese, and gradually, often out of shame and fear for not being understood, they learn to forget their own dialect in order to fit in. Through a small gesture, the act of translating from standard Japanese to Kensengo and not the other way around as they’ve often been told to do, Ofunato Grandmas were given a tool to reclaim the ownership of their language, to appreciate the beauty in a diverse range of connotations that standard Japanese cannot afford, and to resist, gently, the collective forgetting of their own origin.

The second time I watched the film, I just listened to the recitals by the Grandmas without reading the subtitles. In a language I don’t understand, the poems are like songs to my ears. I cannot differentiate between Kensen dialect and standard Japanese, but there is this vibration humming at the end of each line, beautifully delivered in the soft voices of the Grandmas, that makes me tremble. Participants in this translation workshop were the Grandmas of Ofunato, not the intellectuals, not the students in the region. Why is it so? More often than not, the seniors, our Grandmas and Grandpas, are those who are left behind by our society, with the speed of the time they cannot catch up with, the urge to move forward they cannot follow, the refusal of memories. It seems like our desire for development has succeeded in forgetting the slow pace of life, old methods of communication, and intergenerational values that are nothing to us, but everything they used to know. Sometimes I even wonder whether we young generations, through our hi-tech, transactional, outward-looking lifestyles, are made accomplices in the process of marginalizing our seniors on the basis of everyday life.

In the film, poet Arai Takako doesn’t tell us why she hasn’t worked with the Grandpas in the region. But as a woman herself, she must know too well that it is the women, especially those who belong to the generation of Ofunato Grandmas, that are subjected to social exclusion on even more structural levels. Many of them share in the interviews in the film how they were denied of education, thus denied of tools to keep their memories alive. Still, Grandmas persist. They sing, they make poems, and they hold onto memories so rich with aural and oral qualities that transcend time and space.

Songs Still Sung defies any expectation of past traumas being depicted on the screen. No cliché. No crying. No complaints. No aggression. When asked what the ocean—one that hit the region not just once but three times—means to them, one Grandma responds with ease, “I still have to eat their fish.” Looking at the close-up shots detailing the aging of their skin, the absence of their teeth, the whiteness of their hair, the presence of wrinkles, freckles, age spots, injuries, and burns, I cannot help but think how time has sculpted upon their bodies. How many wars, deaths, and upheavals have they been witnesses to? How many personal losses have they endured? Somehow history is literarily etched upon my own Grandma’s memory, making it so rich with details and overflowing with rare vividness and specificity. What I especially like about her is that she doesn’t bother following chronological order and is not at all concerned with telling apart minor from major events, let alone editing out bad from good memories. As a collective, our society often opts to forget, in order to move on. These Grandmas, as much as my own Grandma, remind me how remembering, perhaps with the aid of poetry and oral transmission of stories, can help us reconcile with the past and live more peacefully in the present.

Martin Lukanow

By now, Yang Yong-hi’s family should be used to being shot on film. After all, they’ve been subjected to it for more than two decades, as a means for the director to question not only her family’s dedication to the North Korean regime to the point of sending its sons as presents to the Leader (Dear Pyongyang), but also their multi-decade monetary support of the failing regime.

Many thematic threads begun in Yang’s previous films find their conclusion here. The boyfriend her father pesters Yong-hi about in Dear Pyongyang, is found. He isn’t a Korean, let alone one that supports the North, as her parents would like. Instead, he is from the enemies of the regime—a Japanese—but her mother doesn’t object. Whether it’s because of her onset dementia, or maybe simply because of parental love, is never said. But it doesn’t really matter, because she seems to like him a lot. She makes him samgyetang, a traditional chicken soup, the first day he visits. In a heartfelt scene, she fills the chicken with 40 choicest pieces of Aomori garlic and special ginseng, barely hiding her excitement from her filming daughter.

Later, she teaches the boyfriend, named Kaoru, how to make the soup, and he makes it for her (they eat almost everything, leaving only bones for Yong-hi, who is filming). She even sings him one of her favorite propaganda songs and shows him her treasured portraits of Kim Il-Sung and Kim Jong-Il. He, unlike Yong-hi, seems not to mind the old woman’s zeal for a regime labeled evil by most. Instead, he accepts his partner’s mother’s fervor, urging Yong-hi to do so as well.

Though they might be different, they should still share meals together as a family, he tells her. And for the first time in decades, Yong-hi seems to stop prodding her parents about their political affiliations. It is as if the act of sharing chicken soup has put a halt to her ideological opposition to her parents and somewhat put her mind at ease.

That is not to say that Soup and Ideology is bereft of the political-within-the-intimate themes explored by Yang in her previous films. Here, she chooses not to focus on her mother’s continued dedication to the DPRK, but on her experience during the Jeju Uprising from 1948, a gruesome anti-Communist campaign initiated by Rhee Syngman, the first president of the then supposedly democratic South.

The mother does not disclose this story to her filming daughter, but to a team of researchers visiting her from Korea. Through them, Yong-hi, and we, by extension, learn that the now pro-North Korean activist was only 18 years old and soon to be married to a doctor from Jeju Island. However, her life changed completely when the inhabitants of the island decided to protest the division of the peninsula. This resulted in the police killing them indiscriminately. Her uncle was brutally murdered, as well as her fiancée and many of island’s inhabitants. And with them, their whole families, sometimes entire villages. “If someone from your village was identified among the dead, the entire village would be burned down,” as she tells her daughter for the first time. She was lucky because she could run away to her family in Japan, a country that has functioned both as a home and as a safe haven which would allow her to support the regime she does. In a sense, as explored by the director in her previous film, her mother was allowed to become so engaged with the pro-North Chongryeon precisely because she was living in Japan.

The memories of the South’s violence against the so-called Reds are not presented as a matter of fact. They affect the director’s mother to the point they seem to bring on her Alzheimer’s. In a way, the introduction of the previously unwanted Japanese boyfriend and the forced recall of her past seem to be equally at fault for her disease.

On the other hand, the introduction of Kaoru brings a seismic shift in the movie’s presentation and, from behind the camera, Yong-hi moves in front of it. Though this initially might be necessitated by her mother’s disease and the need for the daughter to have both hands free so she can help her, as the movie progresses there seems to be more to it. It’s as if she’s ready to move from behind the camera and be the judge of everyone in the same way her parents were more than a decade ago. At first, we understand her position only vaguely, but as time progresses, we get to know her better.

This reaches a climax towards the end when the new family, consisting of mother, daughter, and future son-in-law, visit Jeju Island, and the ways the supposedly democratic and pro-American (and by extension, good) government of South Korea treated the island’s citizens come to the surface. In a long scene that is, frankly, difficult to endure for its honesty, Yong-hi seems to manage to finally understand why her mother can’t trust the South. But it’s too late, as the mother’s memories seem to have transferred to the daughter, who has grown weary of the South, instead of her docile mother. Or, at least, she has begun to understand her mother’s dedication towards the North and complete distrust of anything from the South.

In many ways, Soup and Ideology feels like an ending of a story begun more than two decades ago. The movie manages to an end many of the threads started in the director’s first three movies, while giving a way for a new beginning. One open to all possibilities.

Linh Than

Slow-shutter underexposed shots of communal spaces flood the screen with strangers that seem to be too close in proximity. The camera shakes and whips like a paintbrush in a trembling hand, and people’s faces blend into the humble tungsten lights, as well as the night.

Night Shot deals with a heavy theme, rape, a topic that’s infiltrating art more and more recently, but we soon learn that a struggle of this level is anything but incidental. The film is an ongoing 9-year healing journey of the victim (a misnomer really, as she did refer to the experience as both “good and bad”) told in essay format, oscillating between many different modes of narration: black boxes of white texts in the screen center, reports from the police regarding her rape case, her mother’s letters, gynecological test results, and the director’s voice-over. All are layered on top of her daily interactions with the external world while still carrying her wounds, open but invisible, offset by a lot of black frames, and melodies of silence beneath an exquisite sound design.

A disconcerting quietness engulfs the director and the movie, presenting a stark contrast with the vitality of the activities being shot against the backdrop of enhanced natural ambient sounds and creative acoustics. She sits alone, in silence, or reads a poem to herself. She finds refuge in darkness, looking at the world in night-mode, only to find herself scorched by the gentle daytime, during which we see little but a blinding whiteness, a lack of data, of sentiments. It seems like security could only be found in being alone with nature, best portrayed through a touching sequence of tactile interactions with a school of seals. Still, the film is rich in textures: dripping muted paints, washed out clouds and mountains, grass and pavements wheeling her bike,… These are fragments of an agonized life on screen: the film is less a verbal lament, but a physical invitation to feel her pain in just existing. Pain is that powerful, or disempowering, funneling clarity into a floodlight directed straight at us on a lost highway: it hurts if we don’t close our eyes and turn away. Maybe, this is what the film is really about, another dimension of trauma that is out of sight behind our closed eyelids, but could still be felt in solitude.

In modern times where collective movements, like the “me too” movement, political protests, and spoken poetry communities hand women the key to empowerment — their voice in solidarity — moral restitution and justice gradually achieved by trauma articulations still overlook the victim’s solitary rehabilitation: there’s a healing journey much quieter happening at the same time but not at the same pace with the collective on that is shown in this film, that happens only inside out. There is a collective sentiment, but hardly anything called a collective memory, or collective suffering. Official acknowledgement not only disguises behind mimetic empathy, but also marginalizes it. In her own words, the director could barely resurrect the “abysmal” feelings post-rape, but picking up the habit of filming instead. By making the camera her eyes, and making us look through her eyes, the director seeks to purge this normalization and marginalization of personal burdens from which authority and society conveniently disentangle themselves.

At some point, the medley of the outside world: family gatherings, gas-filled protests, laughter, tears, nature,… is periodically muted to embrace silence or acoustical scores, but we can still see actions in frame. We hear more of her voice, firstly after the healing rituals, then through a literal childbirth footage that might symbolize the director’s own rebirth. I take this as a sign of her blocking out external distractions, that her intrepidity is rising from thinning dust, from seeing the world through some tiny, tiny frames, to walking out, hesitantly tracing her steps back to the scene of violation, and from hiding her silence behind others’ noises to speaking out. This act of speaking out for her, though, is much louder than an assertive “me too” to the oblivious crowd: it’s a resolute “me too” to herself, embracing the inevitable coldness of solitude, of her behind-the-scenes battles that are her own to fight. In a world obsessed with moving on, for some people, the only means to move forward is to look back, eyes wide open.

Maybe, all the light that we can see and the sounds that we can hear are all that we can tolerate: this resonates with both the director and society in the way they filter their perception to dodge painful realities. Night Shot is a contest against the systemic impatience and emotional detachment from individual traumas in favor of performative movements. There should be no deadline for healing. The director, as well as survivors of these types of wounds, understands the turbulence inside any stillness, the physical inside the intangible, and the loudness in seemingly quiet solitude. Watching the film reminds me of the existential loneliness in all of us, and how that means we cannot turn our backs to ourselves, even if the world leaves us behind.

Van Do

I have asked I don’t know how many times

but nobody answers my questions

it’s absolutely necessary for the abyss to answer

once and for all, because there isn’t a lot of time left

—Nicarno Parra

It takes only 80 minutes to watch till the end of Night Shot, and probably less than ten minutes to read this text I’m writing. But it’s necessary to be reminded that it took nine years for this film to be born into the world. The director, Carolina Moscoso Briceño, decided to turn the camera to herself after the rape happened to her nine years ago. A “package” of 80 or ten minutes would never do justice to the trauma that has jeopardized her life.

The first few minutes into Night Shot, we are made aware of Carolina’s account of her rape case, which, throughout the film, we know she’s already had to tell so many times. The film then follows her daily interactions, carrying the unhealed wound inside—narrated through her poetic, and somehow utterly vulnerable, ruminations laid bare on screen—and testifying about her case against the medical and legal systems. Towards the end, we read the final words that are the end to her attempts: “I hope your wounds heal through channels outside the law.” This is where the system has failed its people immensely. And cinema is where Carolina turned to as her last resort, a capacious and forgiving one that accompanies her on her healing process.

I lost count of how many times in the film Carolina was rejected by the systems that are supposed to protect her, to work for her. The first time at the hospital after the rape, she asked the doctor for the morning-after pill, a request the doctor refused. The second and third times, she was called to the DA’s office just to be asked the same set of questions, including one implying that she was to blame for being raped: “Didn’t you ask to go out with him?” The fourth time, she was asked to identify the rapist among three presented pictures, to which she responded with 70% certainty. The lack of 30% was later used against her. The fifth time, when she reopened the case after eight years, she was said to be putting herself into a difficult situation because she hadn’t been certain enough and actively engaged enough. It feels like banging one’s head against the wall. “It’s you who have to tell your own story”; “you have to talk”; “your presence is needed”—but when I talk, who is there to actually listen? when I talk, why do I find myself having to repeat myself?

This is a system in which nobody can ever prove enough. It will dismiss you from the most personal choice (the right to your body), see you through certain socially prejudiced lenses (potentially gender-based), cut short the time required for you to mentally recover and consciously participate in the process (rape cases only last for ten years, and five years if the rapist is a juvenile at the time of committing rape). This is a system that prefers box-ticking and reducing gradients into black and white. What is this kind of system that makes its people, especially when they’re most fragile, go through an almost dehumanizing process, rendering them into default true-or-false? If there’s one thing that this system succeeds in doing, it’s creating a labyrinth of procedures and regulations that do their best to exhaust people and make them stop halfway, in short of breath, patience, and dignity to invest in these attempts to claim their rights.

The other day when I chatted with Linh, another participant of the film criticism workshop, we talked about the challenges of making films about current social issues or marginalized groups of people, which are often subjects of interest for many documentary films. Regardless of the creative strategy used to approach the film or the dedication of time and resources in the making of it, such works (to me), often because of a lack of a personal “why” and personal connection to the subjects, are easily prone to imposing an outsider’s somewhat privileged point of view, often with certain predetermined frameworks to link causes to effects. What we rarely get to hear is the deeply personal, the highly particular, the perplexing, even contradicting, persona, that doesn’t package issues into figures and percentages, movements and categories. It’s even worse on the news these days. Competing for reader’s short attention span, news agencies take on the formula of sexualizing and scandalizing crimes, often with intentionally exposed sexual or shocking elements, as bait for clicks and likes.

In Night Shot, I find what exactly is missing. The film amplifies a voice, soft and low, that the world needs to hear more often. Then we will know why victims of sexual assault and rape often cannot be certain, and they cannot be exact. I don’t know anything about the Chilean film scene or culture, neither do I know enough about the filmmaker’s upbringing and background, to know whether she was naturally born with a gift of relating to the world with such nuanced images and the ability to read between the lines. But I like all the metaphors Carolina chooses to live by. These metaphors run through the body of the film as its blood vessels—the night vision function of the camera and our perception in the dark; fire, a lot of fire (the fireplace where she plays guitar, the ritualistic fire of cleansing power, the burning fire that breaks out in a protest), and chlorophyll disease (though the signification of this escaped me).

There is this scene capturing Carolina’s friend giving birth near the end of the film that completely froze me for a while, for the proximity of pleasure and pain, ecstasy and agony, that appeared so visceral and literal, yet so immersive and powerful, on the screen. I have only seen this twice, both times in films, the other time being Stan Brakhage’s Window Water Baby Moving, which also sent chills to my spine.

I have a sense that a winding road still lies ahead for Carolina, but she’s found her home in the cinema somehow. What other kind of system gives you this much space to meander, to get lost, to connect loose dots, to seek refuge in the therapeutic process of self-interrogation? I am in awe of Carolina and her bravery in baring her soul to the world, and of cinema for being a space accepting and elastic enough, particularly in Night Shot, for grief, shame, and fear to play out, and still be allowed.

![ドキュ山ライブ! [DOCU-YAMA LIVE!]](http://www.yidff-live.info/wp-content/themes/yidff-live_2017/images/header_sp_logo1.png)